KELT-9b is an ultra-hot Jupiter-class exoplanet orbits so close to its star that dayside temperatures reach a scorching 4,300 degrees Celsius (7,800 degrees Fahrenheit), hotter than the surfaces of many stars. The extreme temperatures – a record among known exoplanets – are enough to tear apart the molecules making up its atmosphere.

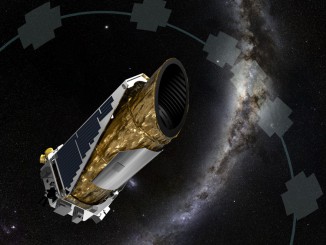

A team of astronomers using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, scheduled to be retired at the end of January, have found evidence that hydrogen gas is torn apart on the side of KELT-9b that’s facing its host star. The molecules reassemble on the slightly cooler night side, only to be ripped apart all over again when the material circulates back around to the dayside.

“This kind of planet is so extreme in temperature, it is a bit separate from a lot of other exoplanets,” said Megan Mansfield, a graduate student at the University of Chicago and lead author of a paper published in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“There are some other hot Jupiters and ultra-hot Jupiters that are not quite as hot but still warm enough that this effect should be taking place,” she added.

KELT-9b was first detected in 2017 using the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope, or KELT, system made up of two robotic telescopes in southern Arizona and South Africa. The researchers used Spitzer to obtain temperature profiles. The data show KELT-9b orbits its star every 1.5 days. It is tidally locked, meaning one side of the planet constantly faces the sun.

Gas and heat, however, flow from one side to the other. The best fit between computer models and the Spitzer observations indicates hydrogen molecules are torn apart on the dayside and then re-assembled in a process known as disassociation and recombination.

“If you don’t account for hydrogen dissociation, you get really fast winds of 60 kilometers (37 miles) per second,” Mansfield said. “That’s probably not likely.”