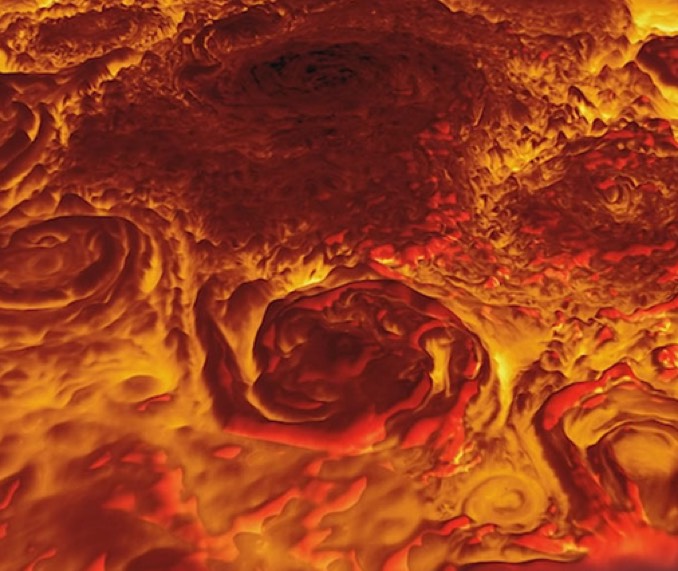

NASA has released an infrared movie of Jupiter’s north polar region as imaged by the orbiting Juno spacecraft’s Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper, or JIRAM, showing a huge cyclone over the north pole surrounded by eight smaller storms ranging up to 4,600 kilometres (2,900 miles) across.

JIRAM can measure temperatures 50 to 70 kilometres (30 to 45 miles) below Jupiter’s visible cloud tops, providing new insights into how the storms are powered. Yellow areas are deeper in the atmosphere and warmer while darker areas are colder and higher. Temperatures range from between -13 degrees and -83 degrees Celsius.

“Before Juno, we could only guess what Jupiter’s poles would look like,” said Alberto Adriani, Juno co-investigator from the Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology in Rome. “Now, with Juno flying over the poles at a close distance it permits the collection of infrared imagery on Jupiter’s polar weather patterns and its massive cyclones in unprecedented spatial resolution.”

During the European Geosciences Union General Assembly in Vienna, Austria, Juno researchers also shared new results shedding light on how the giant planet’s interior rotates.

“Thanks to the amazing increase in accuracy brought by Juno’s gravity data, we have essentially solved the issue of how Jupiter’s interior,” said Tristan Guillot, a Juno co-investigator from the Université Côte d’Azur, Nice, France. “The zones and belts that we see in the atmosphere rotating at different speeds extend to about 3,000 kilometres (1,900 miles).

“At this point, hydrogen becomes conductive enough to be dragged into near-uniform rotation by the planet’s powerful magnetic field,” he said.

Juno researchers also unveiled a new model of Jupiter’s magnetic field based on data collected during the spacecraft’s first eight orbits.

The map shows unexpected irregularities, with more magnetic activity apparent in Jupiter’s northern hemisphere than in the southern. Halfway between the planet’s equator and north pole is an area where the magnetic field is very powerful and positive (seen in red), flanked by areas with less intensity and a negative orientation (blue). In the southern hemisphere, the researchers said, the magnetic field is consistently negative.

Jupiter is generally thought of as a more or less fluid body and it’s not yet known why such differences might be expected.

“We’re finding that Jupiter’s magnetic field is unlike anything previously imagined,” said Jack Connerney, Juno’s deputy principal investigator. “Juno’s investigations of the magnetic environment at Jupiter represent the beginning of a new era in the studies of planetary dynamos.”