Story courtesy Astrobiology Magazine.

As part of the new Gravity Assist podcast, NASA’s Director of Planetary Science Jim Green interviewed David Grinspoon of the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona about the planet Venus and what makes the second world from the Sun so hellish compared to Earth.

Jim Green: Although Venus is about the size of the Earth, it’s very different in many ways. What is happening on Venus that makes it so different?

David Grinspoon: That’s one of the very compelling questions about Venus, because it’s so Earth-like in terms of its bulk properties. If you just ask the most basic questions — what’s its size? What’s its mass? Where is located in the Solar System? You’d say, wow, it’s just like Earth in all these ways. But when you ask what its environment is like, you find that it’s not at all like Earth because it’s so incredibly hot and dry.

When we start talking about Venus today and comparing it to Earth, we’re led to ask not just what’s happening there now, but how has it evolved and how Earth and Venus headed down such different paths. For Venus, it’s a story of having lost its oceans and what we think of as a more pleasant climate a long time ago, and trying to understand this divergence from more Earth-like conditions.

Jim Green: How does Venus help us understand what Earth’s climate is like?

David Grinspoon: It serves as an interesting laboratory for us to test a lot of our ideas about climate and atmospheric processes. Everybody knows about the greenhouse effect on Earth and how carbon dioxide is part of that. Now, picture a planet just like Earth, but where the atmosphere is almost all carbon dioxide. What would that do to the climate? It’s an interesting thought experiment, but it’s also a real experiment because we have this planet next door. Venus, with an atmosphere that is basically all carbon dioxide.

Many other aspects of Earth are exaggerated on Venus, too. You’v heard about acid rain. The clouds on Venus are sulfuric acid, so it’s an extreme case of acid rain. That’s allowed us to study another Earth environmental issue in an exaggerated form.

It makes us smarter about the problems and puzzles that we encounter on Earth, buy seeing them in an altered, and sometimes exaggerated, form on a nearby planet.

Jim Green: What was Venus like early on in its evolution?

David Grinspoon: We have a lot of circumstantial evidence that leads us to believe it was a much more Earth-like planet a long time ago. For instance, there’s the fact that Venus is so incredibly dry today. In fact, if you add up the amount of water on Venus and compare it to what we think is the amount of water on Earth — I say t like that because we don’t actually know how much water is hidden inside the Earth — there’s something like 100,000 times as much water on Earth than on Venus, which is really strange because we picture them probably having formed with roughly the same amount. We think Venus had oceans and a more pleasant climate, possibly even for life, and we’ve got some circumstantial evidence about that.

My best guess is that Venus was much more Earth-like early on. I would say that’s an informed guess, but there’s still a lot of mystery there and a lot of experiments that we’d like to do and measurements we’d like to make to try to pin down that early history much more precisely.

Jim Green: One of the things that’s fascinated me about Venus is that it rotates n the opposite direction, and it rotates very slowly. How has that affected its evolution?

David Grinspoon: Almost all the planets rotate in the same direction as Earth does. If you’re standing on their surfaces, the Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, like we’re used to.

If you were on Venus, assuming that you could see the Sun, which would be very hard because it’s so cloudy there, then he Sun would rise in the west and set in the east. And it would do so very, very slowly, because the planet rotates incredibly slowly [Note: a “solar day” on Venus lasts 116 Earth days.] In fact, if you’re on Venus, you could walk fast enough to keep the sunset in the same place. You could talk as fast as the Sun is moving around the planet. You could watch the sunset forever just by walking.

How that fits into Venus’ evolution is a fascinating question. We don’t fully understand the cause of that. We surmise that it’s related to the early impact history of Venus, just as Earth’s rotation and Earth’s moon are related to the early impact history of the Earth and setting the Earth spinning in a certain way.

The planets formed by these big collisions, and the final few were probably very violent and that way they hit probably influenced that spin. As for Venus rotating in a backwards direction, if you will, we think that probably has to do with large impacts early on in its history, when it was still forming. On Venus, there’s also the fact that there is this incredibly thick atmosphere, almost 100 times as thick as Earth’s, and that can cause a drag on the rotation of the planet through what we call tides, atmospheric tides, where basically the mass of the atmosphere itself is actually pulling on the planet’s rotation over a long period of time. So, that might have to do with how slowly it’s rotating.

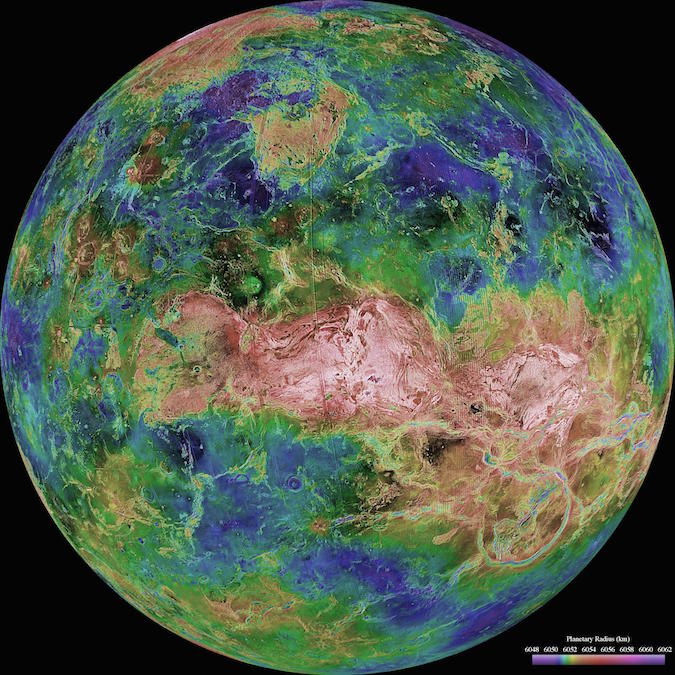

Jim Green: One mission to Venus in particular was Magellan. What was the most important set of observations that came from the Magellan spacecraft?

David Grinspoon: One thing we learned was how volcanically interesting Venus is. Its surface is almost completely covered, in one way or another, with volcanic features, such as broad, flat plains that we think of as flood basalts, like we have on Earth.

Then there are other kinds of volcanoes, such as steep shield volcanoes. I think of Venus almost as a volcano world. The question is, is it still volcanically active? Ever since Magellan, we’ve been trying to nail that down. We think we have some clues about that, but we don’t have a smoking gun telling us that it’s definitely volcanically active.

Jim Green: NASA is currently considering proposals for new missions to Venus. What would you do, from an exploration point of view?

David Grinspoon: There’s certainly a lot more left to explore there, but it is a challenging place. Part of the reason we haven’t been there more is that the surface environment is so severe. You can’t see the surface from orbit, like you can from Mars, at least not in visible light. There are a few things that would really help us with our understanding of its history. One, is that we’ve never really gotten good measurements of the rare gases, what we call the noble gases, and their isotopes Venus’ atmosphere. Other things we would love to do are orbit again with a really much more sophisticated radar.

We now have radar interferometers that on Earth, for instance, can do these amazing measurements where you can actually see the motion of the San Andreas Fault, because they’re so sensitive. If we had something like that on Venus, we could actually see if it’s tectonically active, as well as map the surface in much more detail.

Of course, we would love to land on Venus. The Soviets did it a long time ago, but now, with modern instrumentation and armed with more sophisticated questions, we’d love to dig into the dirt and measure the minerals and really look for clues to the history of that surface and the history of the climate and what happened to the water on Venus.

You can listen to the weekly Gravity Assist podcast here.