The last bits of data collected during NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft’s speedy flyby of Pluto last year are back on Earth, scientists said last week, marking the official end of the probe’s prime mission.

It took more than a year for New Horizons to send back the 50-plus gigabits of data collected around the time the spacecraft zipped by Pluto and its five moons on 14 July 2015.

The data downlinks came down at an average of about 2,000 bits per second — a fraction of the speed of a dial-up Internet connection — and were interrupted as the spacecraft conducted manoeuvres and as ground antennas were needed by other deep space missions.

The long wait for scientists was part of the plan, as officials knew the data stored aboard the probe’s recorders could only come back to Earth a little at a time.

The final data fragment from the LEISA spectral camera within New Horizons’ Ralph instrument arrived at mission control at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, at 0948 GMT on 25 October. The downlink came via an antenna at NASA’s Deep Space Network station in Canberra, Australia, NASA said in a statement Thursday.

It took five hours and eight minutes for the data stream to travel the 5.5-billion-kilometre (3.4-billion-mile) gulf from New Horizons to Earth.

“The Pluto system data that New Horizons collected has amazed us over and over again with the beauty and complexity of Pluto and its system of moons,” said Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “There’s a great deal of work ahead for us to understand the 400-plus scientific observations that have all been sent to Earth. And that’s exactly what we’re going to do—after all, who knows when the next data from a spacecraft visiting Pluto will be sent?”

Mission controllers will conduct a final data verification review before erasing the two data recorders aboard New Horizons, clearing room for future science observations from the spacecraft’s extended mission, which includes a close encounter with the Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69, a frozen world lurking a billion miles beyond Pluto discovered two years ago by scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope.

The next target for New Horizons measures just 21 to 40 kilometres (13 to 25 miles) across, and experts believe 2014 MU69 is a relic building block from left over from the ancient Solar System.

New Horizons will fly by the tiny world on 1 January 2019, at a distance of about 3,000 kilometres (1,900 miles) during an extended mission phase approved by NASA earlier this year.

In the meantime, the New Horizons science team will stay busy combing through the data haul from last year’s Pluto encounter.

“It’s been about a 16-month process, but what rains down are only 1s and 0s,” Stern said in a press conference last week at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting. “Even what comes out of our data reduction pipeline is just raw data. That requires the work of human beings in order to interpret.

“During the entire 16 months, when new datasets were landing several times per week, I think we often felt like doctors in an emergency room, who were just triaging patients one-by-one and stabilising them as quickly as possible to see what was in those datasets,” Stern said.

Scientists prioritised some observations for New Horizons to send back in the first two months after the Pluto flyby. The bulk of the data trickled down over the last year.

“The hard work of really understanding the Pluto system is going to take years,” Stern said last week. “It’s much more complex and nuanced than we ever expected, and we’re happy about that.”

New Horizons scientists presented their latest results last week at the annual Division for Planetary Sciences meeting.

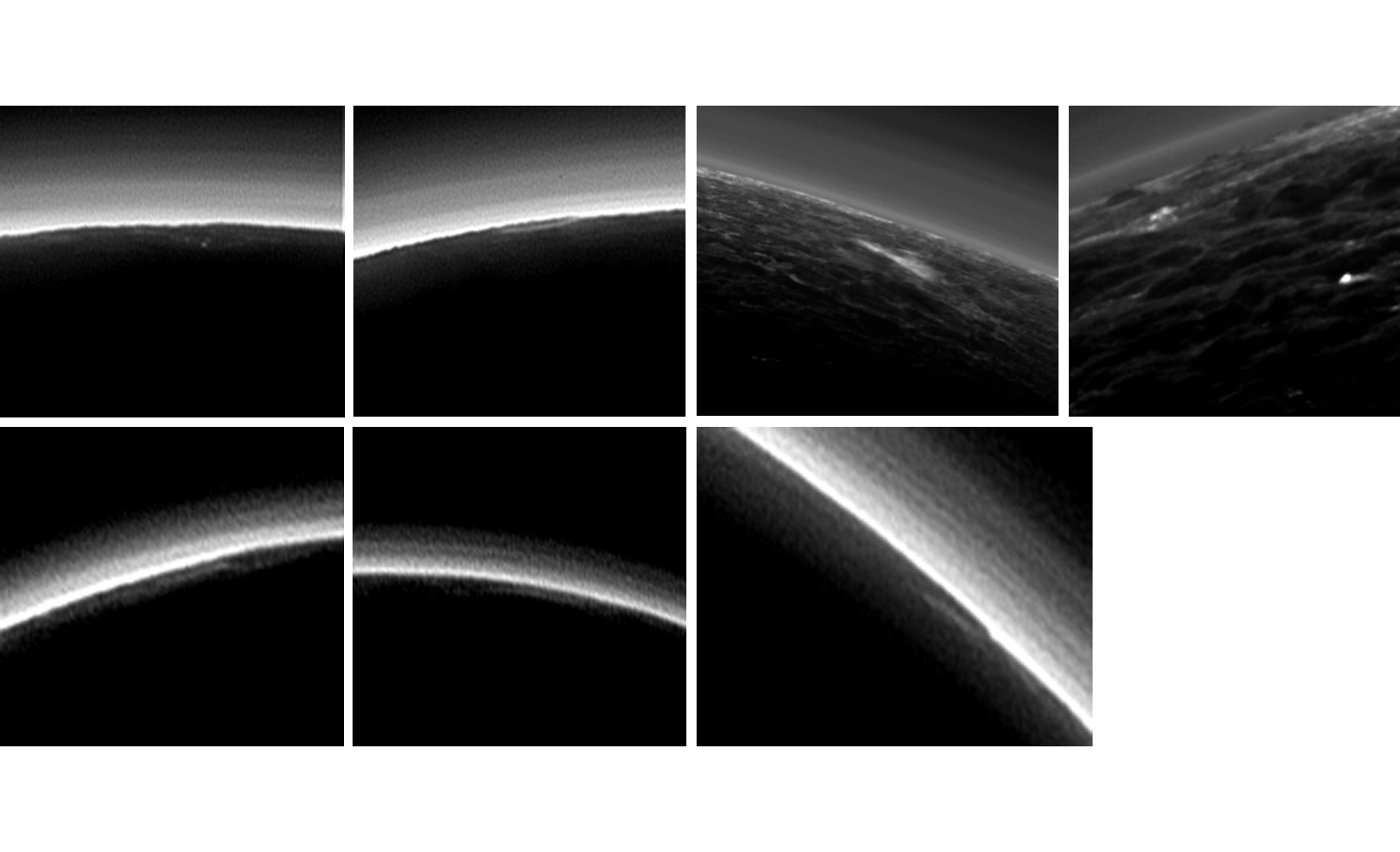

Researchers said they have found several subtle features in pictures captured by the spacecraft’s black-and-white and colour cameras that could be clouds suspended in Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere, which has a surface pressure 100,000 times less than that on Earth.

Scientists identified seven cloud candidates from New Horizons’ imagery, and all are located near the terminator, the boundary between day and night that moves around Pluto during its 6.4-day rotation. They also appear to be lying at low altitudes, and some are in basins surrounded by mountains, but Stern said scientists cannot be sure if the bright regions are clouds floating above the surface, fog at ground level, or some other phenomenon.

Experts would have predicted any clouds at Pluto might form at dawn or dusk at low altitudes, Stern said. A model produced by Erica Barth, a planetary scientist at SWRI, suggests the most likely molecules to form clouds at Pluto would be hydrogen cyanide, light hydrocarbons like acetylene and ethane, or perhaps methane.

Stern said the evidence so far “makes a strong but not airtight case” that some of the features may be clouds.

“We can’t be certain,” Stern said. “There’s a strong circumstantial case that these are clouds, but it’s only a circumstantial case. We can’t definitely say that these are features above the ground. They certainly could be low-lying. In fact, if you take a look at several of the cloud candidates, it looks like they occur in what appear to be topographic lows surrounding constructional mountain features on the horizon.”

While nearly all of Pluto’s atmosphere seen by New Horizons is clear of clouds, the isolated features discovered so far — if they are clouds — could hint to a more complicated and dynamic atmosphere around the frigid dwarf planet.

Some of the earliest images of Pluto beamed back from New Horizons revealed distinct haze layers stretching more than 100 miles above the icy world’s rugged surface.

A final determination of whether the bright patches are clouds will likely require a follow-up mission. That was a common theme of Stern’s presentation last week.

“Like many aspects of the Pluto system, the first flyby has given us a fantastic taste of what’s there in a very dynamic and changing environment, but it’s not enough,” Stern said. “In order to confirm whether there are clouds, we would have to go back, go back with new instrumentation and be there for a longer period with something like a Pluto orbiter.”

Long-range views from the Hubble Space Telescope taken before New Horizons arrived at Pluto showed the dwarf planet to have bright and dark patches, but the probe’s pictures found Pluto to have some of the brightest and darkest areas of any planet-sized object in the solar system.

Bonnie Buratti, a co-investigator on the New Horizons science team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said the brightness of some regions on Pluto — like the Sputnik Planitia area inside the dwarf planet’s famous heart-shaped feature — is tied to geologic activity.

“This active area of Pluto — the heart, or Sputnik Planitia, with the glaciers — is very bright,” Buratti said.

She said other solar system objects, such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus, with similarly reflective regions also exhibit geologic activity. In the case of Enceladus, the activity is manifested in geysers that erupt from a global ocean of liquid water buried beneath the moon’s icy shell.

On Pluto, the bright Sputnik Planitia region has the tell-tale signature of ice flows, likely from slow-moving nitrogen glaciers.

Buratti said the pattern of surface brightness equating to activity could be extended to unexplored worlds residing in the Kuiper Belt, a doughnut-shaped ring of icy proto-planets beyond the orbit of Neptune.

One such world is Eris, the most massive known object in the Kuiper Belt and the largest known dwarf planet not visited by a spacecraft.

“We wouldn’t be surprised if we went to Eris and saw that it’s also active,” Buratti said. “This is something we can infer just looking at a pinpoint of light and combining it with our spacecraft observations (at Pluto).”

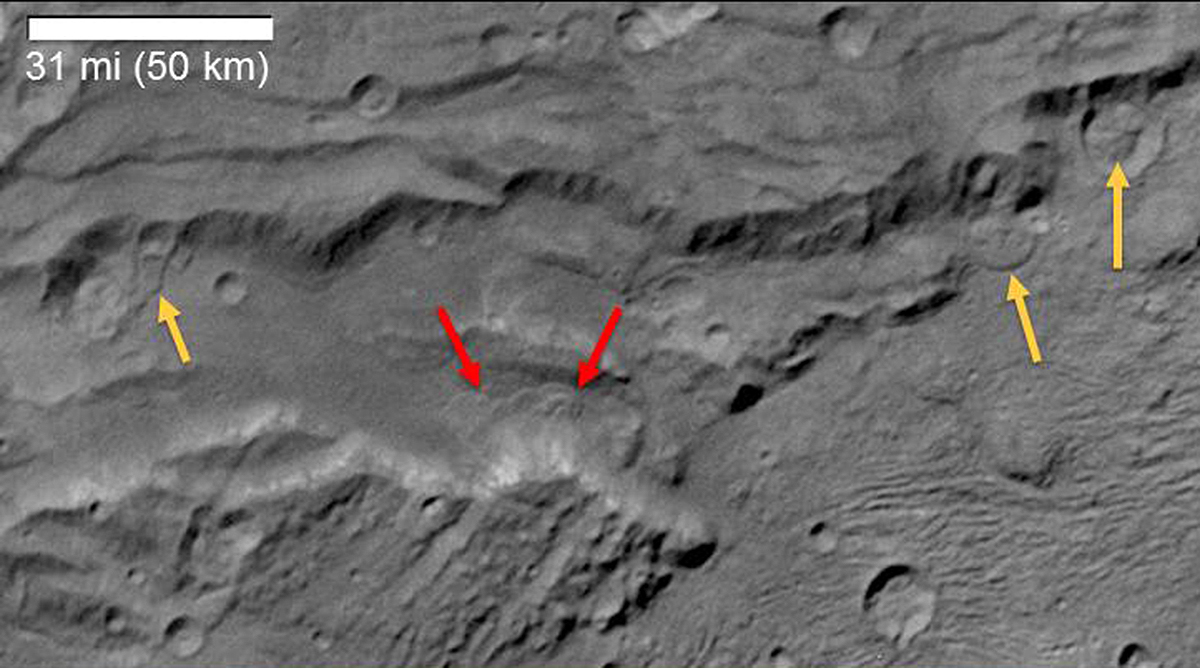

Scientists also announced the discovery of landslides on Pluto’s largest moon Charon.

New Horizons’ LORRI imager detected signs of long run-out landsides on the walls of a canyon on Charon named Serenity Chasma, where rocks and other surface material fell down a 30-degree slope and left a deposit as thick as 200 metres (650 feet).

The slides could have been triggered billions of years ago by a quake or a violent impact that shook Charon, according to Ross Beyer, a science team researcher from Sagan Center at the SETI Institute and NASA’s Ames Research Center.

No such landslides have been found on Pluto.

“Landslides have been detected on Charon,” Beyer said. “They are the first landslides that we have seen in the Kuiper Belt. We wonder if they will be detected elsewhere in the Kuiper Belt if we go to other places there and see their geology, but of course, to do so requires new missions to the Kuiper Belt to find that out.”

Officials are already discussing the next step in the exploration of the Kuiper Belt after New Horizons, but a decision to fund any NASA-led mission to return to the outer frontier of the solar system will be weighed against the merits of launching probes to other planets, such as orbiters to conduct the first in-depth surveys of Uranus, Neptune and their extensive moon systems.

NASA is already looking at concepts for potential missions to Uranus and Neptune for consideration by the National Research Council’s decadal survey, a major review held every 10 years to set priorities for the space agency’s solar system research and exploration.

In the last decadal survey published in 2011, the top two recommendations made by an independent panel of senior scientists were for NASA to pursue the first step in a multi-mission effort to return samples from the surface of Mars and to start development of a probe to study Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Both projects are now in NASA’s development pipeline with the agency’s next Mars rover, which will prepare samples for retrieval by a future spacecraft, and a two-part flagship-class mission to repeatedly fly low over Europa with a flyby probe and land a science station on the moon’s icy crust.

The third priority for NASA’s planetary science division in the 2011 decadal survey report was a Uranus orbiter.

The National Research Council’s next planetary science decadal survey is due out in the early 2020s.

“We are starting to look at the studies to support the next decadal survey,” said David Schurr, deputy director of NASA’s planetary science division. “(A Kuiper Belt mission) would trade against other very interesting objects in the solar system, including a lot more of the outer planets which we haven’t yet explored.”

NASA has approved funding for studies of potential Uranus and Neptune orbiters, but no such study has yet started for a second mission to the Kuiper Belt.

“We’re at the very beginning stages in our science team, and in the broader science community, in starting to talk about what the right follow-ups are in the Kuiper Belt,” Stern said. “Some advocate missions to other small planets in the Kuiper Belt to look at the diversity … Some are advocating going back to Pluto to study it in more detail. It’s all extremely early days.”

Stern said one early concept for a Pluto orbiter could have it launch on NASA’s heavy-lift Space Launch System and reach the dwarf planet seven-and-a-half years later, using a nuclear generator to power its science instruments and electric-ion thrusters to spiral into orbit once the craft arrives.

But no such mission is on NASA’s drawing boards.

New Horizons will have to do for now, with its mission funded through 2021, when the spacecraft will have radioed home all its data from the flyby of 2014 MU69.

“We’ve never been to anything like MU69, something that’s been cold for the entire 4 billion years (since the early solar system), and that, in addition, is small enough to not have the same degree of geological processes that we see on Pluto and Charon, much more massive objects that have planetary processes on them,” Stern said.

Telescopic observations show 2014 MU69 is redder than Pluto in natural light, but not as red as Mars. That indicates the object is part of the primordial disk of rocks and boulders that formed the planets, according to Amanda Zangari, a New Horizons post-doctoral researcher from Southwest Research Institute.

Scientists hope to learn the object’s rotation rate and shape before New Horizons arrives. That measurement would allow engineers to tweak the probe’s trajectory to fly by when 2014 MU69’s broadest side faces New Horizons’ cameras.

On the way in, New Horizons will search for tiny moons that could accompany the target.

“This is a completely new kind of world that we’re going to,” Stern said. “It’s somewhere in the vicinity of 1,000 times the mass of Rosetta’s comet (67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko) and yet only 1/10,000th the mass of Pluto.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.