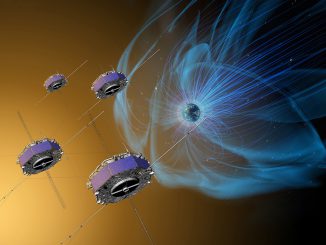

In this study, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, scientists compared ground-based videos of pulsating aurorae — a certain type of aurora that appears as patches of brightness regularly flickering on and off — with satellite measurements of the numbers and energies of electrons raining down towards the surface from inside Earth’s magnetic bubble, the magnetosphere. The team found something unexpected: A drop in the number of low-energy electrons, long thought to have little or no effect, corresponds with especially fast changes in the shape and structure of pulsating aurorae.

“Without the combination of ground and satellite measurements, we would not have been able to confirm that these events are connected,” said Marilia Samara, a space physicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author on the study.

Active aurorae happen when a dense wave of solar material — such as a high-speed stream of solar wind or a large cloud that exploded off the Sun called a coronal mass ejection — hits Earth’s magnetic field, causing it to rattle. This rattling releases electrons that have been trapped in the tail of that magnetic field, which stretches out away from the Sun. Once released, these electrons go racing down towards the poles, then they interact with particles in Earth’s upper atmosphere to create glowing lights that stretch across the sky in long ropes.

On the other hand, the electrons that set off pulsating aurorae are sent spinning to the surface by complicated wave motions in the magnetosphere. These wave motions can happen at any time, not just when a wave of solar material rattles the magnetic field.

“The hemispheres are magnetically connected, meaning that any time there is pulsating aurora near the north pole, there is also pulsating aurora near the south pole,” said Robert Michell, a space physicist at NASA Goddard and one of the study’s authors. “Electrons are constantly pinging back and forth along this magnetic field line during an aurora event.”

The electrons that travel between the hemispheres are not the original higher-energy electrons rocketing in from the magnetosphere. Instead, these are what’s called low-energy secondary electrons, meaning that they are slower particles that have been kicked up out in all directions only after a collision from the first set of higher-energy electrons. When this happens, some of the secondary electrons shoot back upwards along the magnetic field line, zipping towards the opposite hemisphere.

When studying their pulsating aurora videos, researchers found that the most distinct change in the structure and shape of the aurora happened during times when far fewer of these secondary electrons were shooting in along hemispheric magnetic field lines.

“It turns out that secondary electrons could very well be a big piece of the puzzle to how, why, and when the energy that creates aurorae is transferred to the upper atmosphere,” said Samara.

However, most current simulations of how the aurora form don’t take secondary electrons into account. This is because the energy of the individual particles is so much lower than the electrons coming directly from the magnetosphere, leading many to assume that their contribution to the glowing northern lights is negligible. However, their cumulative effect is likely much larger.

“We need targeted observations to figure out exactly how to incorporate these low-energy secondary electrons into our models,” said Samara. “But it seems clear that they may very well end up playing a more important role than previously thought.”