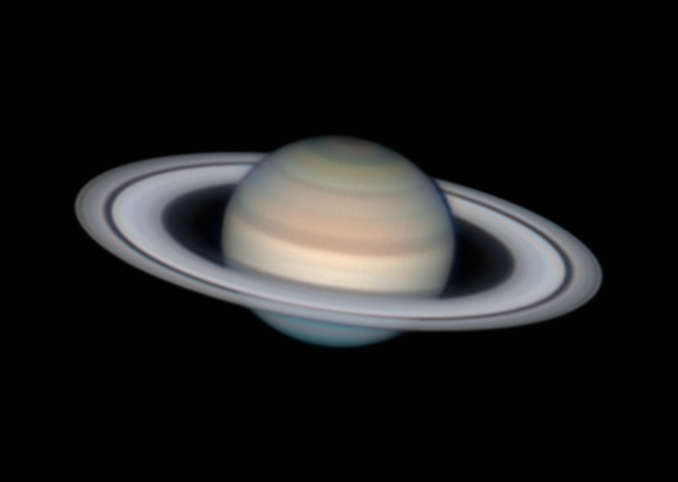

Saturn comes to opposition on the night of 1/2 August in one of the highlights of the observing year. Saturn is often described as the jewel in the Solar System’s crown and after one look at its majestic system of rings through a telescope, who would argue? Nobody ever forgets the first time they see Saturn sail serenely into the field of view. That beautiful sight can still move experienced, seen-it-all-before observers and galvanise casual first-timers to explore further and gain a life-long interest in the night sky.

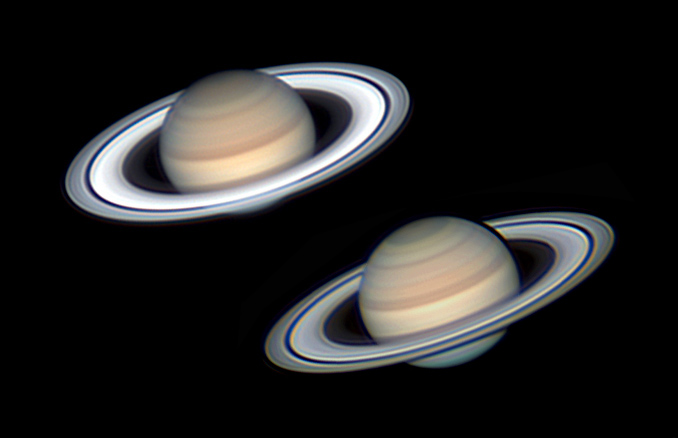

The good news is that an observatory class telescope or an expensive, sophisticated imaging set-up is not needed to get a good view of the ringed wonder. An 80–90mm (~three-inch) telescope operating at 50x can show Saturn’s two main rings, Rings A and B, as separate structures, as well as show the flatness (oblateness) of Saturn’s globe (its flatter than Jupiter, with its polar diameter being about 11 per cent less than that at its equator) and pick out Saturn’s giant moon Titan.

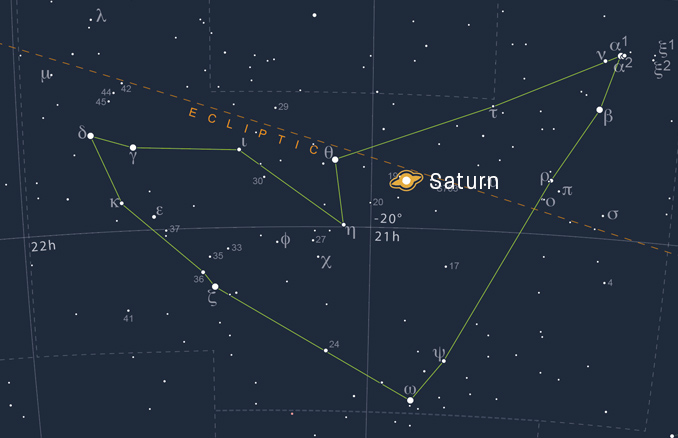

There’s less good news for finding and observing Saturn at this year’s opposition. Saturn lies well south of the celestial equator (declination ~ –18°) among the stars of Capricornus. This is an advantageous location for our observing colleagues in the Southern Hemisphere, but presents a number of hurdles for those of us hoping to view Saturn from mid-northern latitudes including from the UK.

The constellation of Capricornus is a bit of a roof-top scraper; magnitude +4.8 eta Capricorni lies roughly at the centre of Capricornus’ territory and culminates on 2 August at barely 18 degrees altitude from London. The situation deteriorates the farther north one goes; from Edinburgh, the star peaks at an elevation of around 14 degrees. Saturn lies around 1.5 degrees north of eta during August, so at best it’ll climb to an altitude of just 20 degrees or so.

Observing any astronomical body at an altitude of less than about 30 degrees introduces destructive seeing conditions. The closer to the horizon your chosen object lies, the more of Earth’s atmosphere you are having to look through and the more your view deteriorates and the brightness of the object decreases. Atmospheric dispersion causes noticeable colour effects such as red and blue fringing on planets, caused by our atmosphere acting effectively as a prism.

Despite this gloomy scenario, it’s a certainty that a patient observer will benefit from fleeting moments of steady seeing or experience an exceptionally fine night, when Saturn and its rings snap into sharper focus and make everything right! Astronomy Now has recently received remarkable observations and images of Saturn taken from the Northern Hemisphere, so don’t let the planet’s low altitude put you off observing it at any opportunity.

On opposition night, Saturn shines at magnitude +0.2 and rises between about 8.40pm and 9.10pm BST (earliest from the south of England) and crosses the southern meridian (culminates) between just after 1am and 1.20am BST. It’s best to observe Saturn while it’s within an hour or so of culmination.

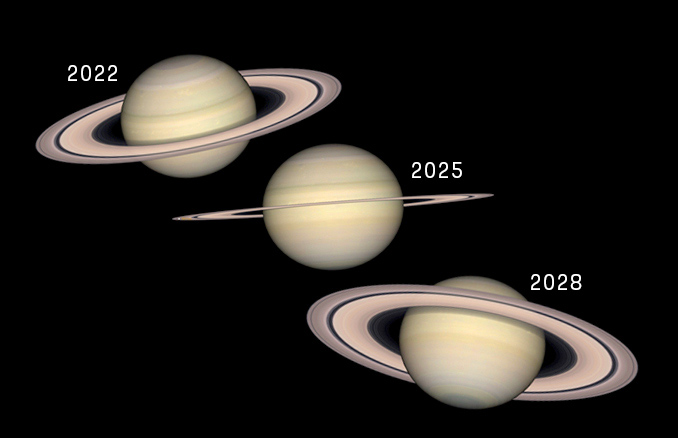

Saturn sports three major rings that can be seen and imaged by amateur astronomers. Ring A is the outermost ring and is separated from the broadest and brightest ring, Ring B, by the famous Cassini Division. You’ll probably need a 250mm (ten-inch) telescope to see the dark Cassini Division. If you can get hold of an Atmospheric Dispersion Corrector (ADC), then you may spot closest to Saturn’s distracting globe the notoriously difficult and dark Ring C, also known as the Crêpe Ring, and the elusive Encke Gap, or Encke Division, which bisects Ring A.

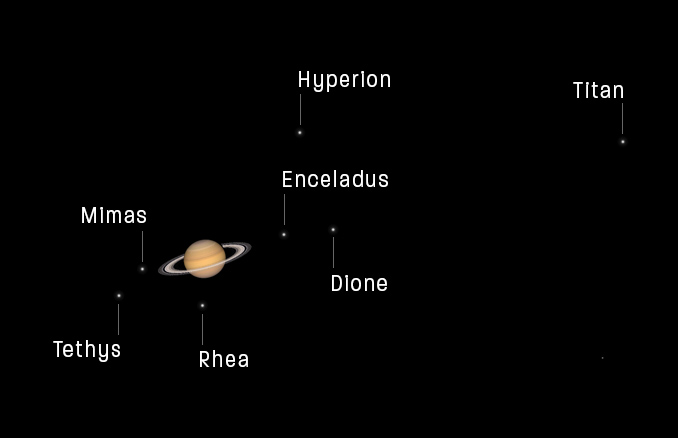

Eight of Saturn’s moons – Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, Hyperion and Iapetus – are visible through amateur instrumentation. Titan is always easy to see through a small telescope, while a large telescope may be able to show Rhea, Tethys and Dione (see the graphic below for their positions on opposition night).

August is an exciting astronomy month, as once we’re done with Saturn the marvellous Perseid meteor shower, this year free from interference from moonlight, peaks on 12/13 August. Then mighty Jupiter is in the spotlight when it too reaches opposition on 19/20 August.