1–7 June 2009

Deep Sky

Beginner's Visual Challenge of the Week:

NGC 6210

Use this chart to locate the planetary nebulae in Hercules.

Graphic made from using The Sky version 5 http://www.bisque.com/sc/pages/thesky6family.aspx

Hercules is mainly known for hosting the magnificent globular clusters M13 and M92 and its ‘keystone’ asterism. Also worth more than a passing glance is the diminutive planetary nebula NGC 6210, which makes a nice challenge for owners of small telescopes.

It’s not a faint apparent magnitude, common for many other planetaries, that makes this planetary a tough proposition. It’s tiny apparent size of only 30 arcseconds, less than a third that of M57, the Ring Nebula, is the obstacle to its detection. Perhaps it was this that caused the Herschel to miss it and its discovery in 1825 was credited to the double star observer Otto Struve, who used a 9.6-inch refractor. NGC 6210 is listed as magnitude +8.8 and should be visible in telescopes in the 80mm–100mm class, although high magnification will be needed to show it as clearly non-stellar, like an out of focus star. It is very strongly coloured, appearing blue or greenish to many observers’ eyes and this will help you pick it out. Start with low power to acquire the field, and then ramp up the magnification as far as the conditions will allow you to observe it.

In 1998 a Hubble Space Telescope image gave rise to the nebula’s nickname of the ‘Turtle Nebula’, and large telescopes may show the jets that form the ‘flippers’. At least the nebula’s non-circular shape and some detail in its disc should be discernable through filters, if the seeing allows for high powers. Colour CCD images can produce spectacular results.

To track down this diminutive gem, start at beta (β) Herculis, a third magnitude star found ten degrees south of the Keystone, the trapezoid formed of eta (η), zeta (ζ), epsilon (ε) and pi (π) Herculis. Then move four degrees north-west to a wide pair of seventh magnitude stars, one of which is a double. Our target is located a few arcminutes north-west of the single star. You can find a picture of it on Adam Block's website here.

There are two other planetaries in Hercules, both considerably fainter than NGC 6210, but well worth a look all the same. NGC 6058 is roughly the same size as the ‘Turtle’ but is much fainter, glowing at a photographic magnitude of +13.3. It lies near the Corona Borealis border, about eight degrees north-west of M13. IC 4593 is brighter at photographic magnitude +10.9 and roughly the same size again. Both will require large telescopes with filters to track down.

Deep Sky Object of the Week:

Messier 101

Galaxy M101. Image: Nik Szymanek.

M101 was a last minute addition to the third version of Messier's catalogue but its lowly position belies its magnificence as a giant, face-on spiral galaxy, and the third largest galaxy in the catalogue by apparent size. Pierre Méchain discovered M101 in March 1781 and William Herschel observed it in April 1789, discovering what we now know are the giant HII Regions NGC 5461, 5462 and 5447.

M101 (NGC 5457) is the archetypal ‘grand design’ spiral galaxy, seen face-on to us in the splendid constellation of Ursa Major. It lies 21.7 million light years away and its apparent size of 29 x 27 arcminutes equates to an actual diameter of 184,000 light years, almost twice the size of our own Milky Way galaxy! Its magnificent spiral arms are peppered with HII regions and ten of these have individual NGC designations. Many of these bright knots have masses that rival dwarf galaxies, perhaps some ten million Suns. One in particular, NGC 5471, is two orders of magnitude larger and brighter than anything in the Milky Way.

M101 appears quite bright to us and its catalogued magnitude of +7.7 brings it within reach of 10 x 50 binoculars. Small telescopes easily show M101 as a featureless oval patch with a bright core. In common with most face-on spiral galaxies, M101 has a low surface brightness, which makes parts of it appear dim with the spiral arms requiring quite large telescopes to trace. Some of the brightest star clouds start to become apparent in telescopes around 100mm–150mm in size and on dark, transparent nights a 200mm telescope reveals a halo of hazy nebulosity and perhaps a hint of the spiral structure. Much more detail become apparent when using apertures in the 300mm–350mm range, including multiple, weakly defined spiral arms, but it really takes CCD images to fully reveal M101’s full majesty.

Locating M101 is fairly easy – it lies just over five degrees from Alkaid, the star at the end of the Plough’s handle. There’s also a nice star-hop from Mizar, in the Plough, eastwards along the line of fifth and sixth magnitude stars, 81, 83, 84 and 86 Ursae Majoris. It is circumpolar from the UK (always above the horizon), and this week is 60 degrees up at 1am. Obviously June is not the ideal month for deep sky observation, especially for northern regions of the UK. The Moon doesn’t help either by waxing to full this week, but the early summer ecliptic is very low in the southern sky and the Moon lies low down in Scorpius, negating much of its overpowering glow. Why not give it a go, as M101 will not disappoint.

Use this finder chart to locate M101 . Graphic made using The Sky version 5 http://www.bisque.com/TheSky/

Deep Sky Challenge:

Palomar globular clusters

Palomar 1 imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Image: NASA/ESA/Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA).

Almost all observers will be very familiar with the large, bright globular clusters such as M13, M3 and M5, with Omega Centauri and 47 Tucanae sweeping all before them in the Southern Hemisphere. Many of the remaining clusters were observed by William and John Herschel, receiving NGC designations and together with the odd IC number; the vast majority are not regarded as particularly challenging objects. Enter the Palomar Globular Clusters.

Examination of the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey plates, taken with the 48-inch Oschin Schmidt Telescope in the 1950s, led to the discovery of many new objects, including 15 new globular clusters. These are challenging objects for the imager and visual observer alike, as most are faint and small, ranging from magnitude +9.4 to +14.7 and are 42 arcseconds to ten arcminutes in size. I realise June is far from ideal to go tracking down such faint quarry, but many have high northerly declinations and are observable under better conditions. It is really a long-term project but there are a number of them that can be imaged this week by observers with long focal length telescopes, such as Schmidt–Cassegrains operating at f/10 or f/11.

Palomar (Pal) 1 lives in Cepheus at RA 03h 33m 58.3s, Dec +79° 36’ 07”; this week Cepheus is high in the north-eastern sky by 1am, with Pal 1 forty degrees up. It is listed at magnitude +13.6 and 2.8 arcminutes in size, so to attempt it visually will require a very large telescope operating at x200 power at least. The nearest ‘bright’ star is tenth magnitude SAO 4929, some eight arcminutes north of Pal 1. It is reportedly more difficult than its listed magnitude.

This finder chart for Palomar 1, and each of the following charts, are roughly one degree across and should help locate the field of each Palomar globular. All graphics are made with Megastar version 5 http://www.willbell.com/SOFTWARE/MEGASTAR/index.htm

Pal 10 can be found in the small but distinctive constellation of Sagitta, five degrees west of alpha Sge and 2.5 south-west of the famous Coathanger asterism in Vulpecula (co-ordinates are RA 19h 18m 16.0s, Dec +18° 34’ 32”). Come 1am, it is a healthy 45 degrees above the south-eastern horizon. It is larger than Pal 1 at four arcminutes across but roughly the same magnitude, +13.2.

Palomar 10 finder chart.

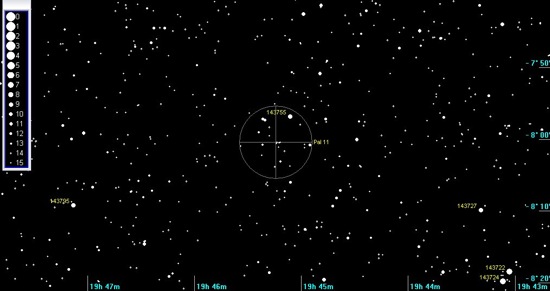

Pal 11 is located in the southern reaches of Aquila at RA 19h 35m 31.0s, Dec –07° 59’ 50”, two arcminutes south-east of fifth magnitude kappa Aquilae. The brightish star SAO 143755 (magnitude +8.9) is a few arcminutes north-west of the centre of the cluster. Pal 11 is listed at magnitude +9.8 and is 10 arcminutes in size, so potentially it is one of the easier globulars on the Palomar list, although its southerly declination won’t help UK observers. Pal 11 is a nearby cluster of average size that is heavily obscured by dust.

Palomar 11 finder chart.

Our final Palomar is Pal 14, a giant cluster located far away in the Milky Way’s outer halo. It is located at RA 16h 11m 14.5s, Dec +14° 56’ 44” in southern Hercules, eight degrees south-east of beta Herculis. There is a pair of ninth magnitude stars, SAO 101993 and SAO 101983, about 12 arcminutes to Pal 14’s north-east and south-west respectively. It culminates at about 12:20am at over 50 degrees elevation. At magnitude +14.7, Pal 14 is supposedly of all the Palomar clusters, but reports suggest Pal 15 in Ophiuchus is a more difficult object.

Palomar 14 finder chart.

The BAA Deep Sky section (http://britastro.org/baa/content/blogsection/6/129/) has an ongoing project to observe and image all the Palomar clusters and many CCD images have already been received, some of them imaged in June 2008. If you are successful in obtaining images or visually, then Astronomy Now and the BAA’s Deep Sky section director, Stewart Moore, would be delighted to hear from you. In fact, even negative visual observations can be useful, as long as details of equipment and sky conditions are given. Happy Hunting!

Solar System Round-Up

|