U.S. laboratory produces first plutonium in 25 years

BY STEPHEN CLARK

SPACEFLIGHT NOW

Posted: 20 March 2013

HOUSTON -- For the first time in 25 years, the United States is producing plutonium fuel to power spacecraft on missions beyond Earth, replenishing a dwindling stockpile to supply NASA's next Mars rover and other proposed probes.

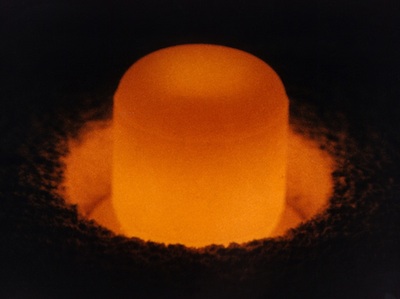

Photo of a pellet of plutonium-238. Credit: U.S. Department of Energy

"This is a major step forward," said Jim Green, head of NASA's planetary science division.

NASA uses plutonium when solar arrays are unable to power spacecraft visiting the outer solar system. Nuclear generators have powered 27 U.S. space missions over the last five decades, enabling exploration of the sun, the moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. NASA's Curiosity rover exploring Mars is powered by plutonium, and the New Horizons probe, another nuclear-powered mission, is cruising toward Pluto for an encounter in 2015.

The milestone comes after Congress and the White House struggled to restore funding to artificially create plutonium-238, the special non-weapons grade isotope used to generate electricity for space missions.

The U.S. Department of Energy is overseeing the plutonium production project at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, and NASA is the chief customer of the effort.

The agencies intended to divide the costs of restarting plutonium-238 production, which ended in 1988. But Congress refused to appropriate the Energy Department's share of the plutonium funding, leaving only NASA's half of the money to pay for production.

The Energy Department produced the plutonium in existing facilities at Oak Ridge to save costs.

"They have developed a series of processes that have encapsulated neptunium-237 and put it in a reactor at Oak Ridge, irradiated it for a month, and now the analysis is clear that we did indeed generate plutonium," Green told a meeting of Mars scientists in late February.

So far, the experiments at Oak Ridge's High Flux Isotope Reactor are only producing small amounts of plutonium-238, Green told attendees at the 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference near Houston.

Green said Energy Department officials are developing procedures to safely handle larger quantities of plutonium-238.

"We expect reports back from them later this year on a complete schedule that would put plutonium-238 on track to be generated at about a kilogram-and-a-half (3.3 pounds) or so a year," Green said.

But it could take five years for enough plutonium to be produced to put in a spacecraft, according to NASA.

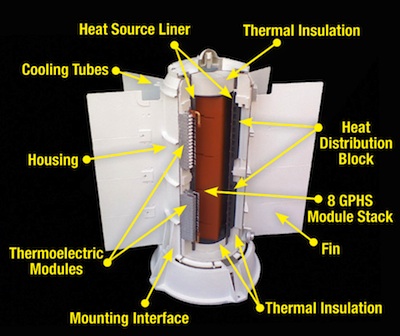

Diagram of a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator like the unit powering the Curiosity rover on Mars. Credit: NASA

The Energy Department has lost some of its aging plutonium supply due to radioactive decay.

Scientists will blend one kilogram of the new plutonium with every two kilograms of older material to create a mixture with the appropriate energy density for space applications, according to Green.

"Things are looking really good for us to be able to start resupplying plutonium into our stockpiles," Green said.

The Energy Department does not disclose how much plutonium it has in storage, but the Aerospace Industries Association says stockpile will be exhausted after one more large flagship-class nuclear-powered space mission.

NASA plans to launch a copy of the Curiosity Mars rover in 2020, and the robot will likely be powered by a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, or MMRTG. Each MMRTG includes about 8 pounds of plutonium and converts the heat of the isotope's radioactive decay into electricity.

The space agency's solar system exploration program has been scaled back in recent years. NASA has deferred development of a plutonium-powered robotic mission to Europa, and other probes requiring nuclear fuel could use a more efficient electrical generator using less plutonium than the MMRTG.

But with the Energy Department's supply of plutonium-238 nearly depleted, any NASA mission to the outer solar system would be grounded without new plutonium production.

The U.S. government purchased much of Russia's plutonium-238 stockpile, taking deliveries from 1992 until the late 2000s before Russia stopped exporting the material.

|