Moonlets batter

Saturn’s F-ring

AMANDA DOYLE

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: 28 March 2012

The gas giant Saturn is most famous for the set of dazzling rings that encircle the planet, and new images have revealed that “jets” streaming from its F-ring are caused by collisions of moonlets with the ring.

Saturn’s F-ring is situated several thousand kilometres beyond the main ring system, and was discovered by Pioneer 11 in 1979. The thin ring is only a few hundred kilometres across, compared to other rings which span thousands of kilometres, and it is shepherded by the moons Prometheus and Pandora.

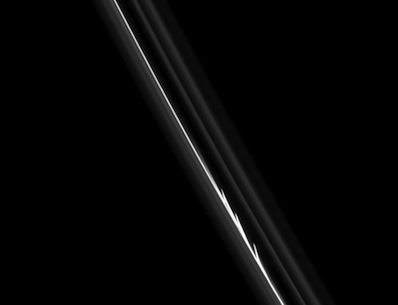

The “jets” visible in Saturn’s F-ring are caused by collisions of small objects with the ring. Image: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

These moons cause perturbations to the ring, but the F-ring also suffers from another anomaly in the form of “jets”. These jets can extend for hundreds of kilometres and are caused by objects colliding with the ring, such as the moonlet S2004/S6.

Smaller jets have also been discovered, but these are typically difficult to observe as they only persist for several hours or days. However, as NASA’s Cassini spacecraft was imaging the moon Prometheus for half an orbit, it also captured a series of images of one of these micro-jets.

Nick Attree from Queen Mary, University of London, revealed the details of this particular micro-jet at the National Astronomy Meeting in Manchester. The jet was seen to stretch for 50 kilometres, before collapsing back in towards the F ring. In addition, the distance between the tip of the jet and the core of the ring was measured to be around 27 kilometres.

The culprit that caused this jet is thought to be a small moonlet, around one kilometre across, that collided with the ring at a velocity of one metre per second. This low velocity indicates that the moonlet was a local object on a similar orbit to the F ring, since if it had come from elsewhere it would have been moving at a greater velocity. Attree added that it is likely that some of these moonlets get destroyed completely when they impact with the F-ring.

Attree hopes that future work on these micro-jets – of which some 570 events have already been observed – will put constraints on the size, distribution and orbits of the colliding moonlets, as well as improve the general understanding of low velocity collisions between icy objects.

|