The Milky Way's stray stars

DR EMILY BALDWIN

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: 11 January 2012

Results from the Sloan Extension for Galactic Understanding and Exploration 2 (SEGUE-2) survey shows that the Milky Way disc grew from the inside out, but that some stars have wandered far from the plane of the Galaxy on unusual orbits.

SEGUE-2 is part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey SDSS-III project, which has tracked the motions and measured the compositions of over 118,000 stars. Principal Investigator Connie Rockosi of the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) leads a team that is investigating why some stars in the Milky Way's disc – the bright band of stars that we can see in the night sky and call the Milky Way – orbit far above and below the plane of the Galaxy's disc.

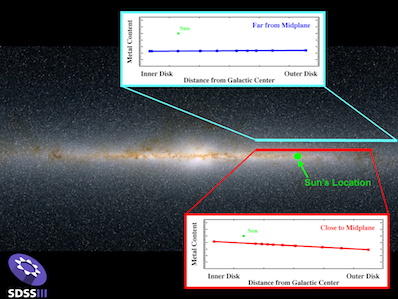

Measurements of the metal content of stars in the disc of our Galaxy. The bottom panel shows the decrease in metal content as the distance from the Galactic centre increases for stars near the plane of the Milky Way disc. In contrast, the metal content for stars far above the plane, shown in the upper panel, is nearly constant at all distances from the centre of the Galaxy. The background image of the Milky Way is from the Two-Micron All Sky Survey. Image: Judy Cheng and Connie Rockosi (University of California,

Santa Cruz) and the 2MASS Survey.

Studying the unique chemical compositions of these non-conforming stars and comparing their properties with stars in other locations provides insight into how the Milky Way grew and how these stars came to be wandering in unusual orbits.

The first generation of stars consisted entirely of hydrogen and helium, with subsequent generations fusing heavier elements such as calcium and iron. By studying the stars' the metal content – any elements heavier than hydrogen and helium – astronomers can learn which parts of the Galaxy have hosted the most generations of star.

The SEGUE-2 team found that stars closer to the core of the Galaxy have a higher metal content than those further from the centre. “That tells us that the outer disc of our Galaxy has formed fewer generations of stars than the inner disc, meaning that the Milky Way disc grew from the inside out,” says Judy Cheng, also of UCSC. But this trend only seems to apply to stars that orbit in a flat plane around the centre of the Galaxy; for the stars orbiting above and below the plane, the stars showed a low metal content, regardless of their distance from the heart of the Galaxy.

“The fact that the metal content of those stars is the same everywhere is a new piece of evidence that can help us figure out how they got to be so far away from the plane,” adds Rockosi.

Where these stars born with these orbits, or did they get a nudge from some outside influence? “If these stars were born with these orbits they were born at the same rate all over the galaxy,” says Cheng. “If they were born with regular orbits, then whatever happened to them must have been very efficient at mixing them up and erasing any patterns in the metal content, such as the inside-out trend we see in the plane.”

This mixing could have come from a past collision between our Galaxy and a neighbour, or might be due to the effect of the Galaxy's spiral arms sweeping through the disc.

"We think it is unlikely that all of these "different drummer" stars came from other galaxies," Cheng tells Astronomy Now, adding that there are two further lines of research her team would like to pursue to find the answer. "First, we are looking at other properties of the stars in our sample, including the abundances of other elements, as some elements can tell you how much time passed between successive generations of stars, which will add another dimension to what we know from the overall metal content. Second, we would like to work with researchers who are simulating the formation of the disc. If simulations show that interactions with other galaxies or the disc's spiral arms cannot mix stars around the disc well enough, then the rapid formation scenario is the one that better fits what we have observed with SEGUE".

|