|

|

Supernova next door leaves its origin in its ashes

GEMMA LAVENDER

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: 20 December 2011

You have to be pretty quick to catch the explosive nature of a Type Ia supernovae in the act, however, it seems that an international collaboration of astronomers have gone one better by catching one of these violent blasts in its early stages, for the first time ever, just 11 hours after its detonation. Nestled in the Pinwheel Galaxy, the supernova, dubbed SN2011fe resides just an astronomical stone’s throw away at a distance of 21 million light years from Earth, crowning it the closest of its kind for 25 years.

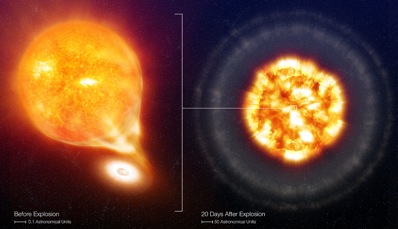

Before and after: a white dwarf accretes matter from a sun-like star (left), until it accumulates so much mass that it exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit (1.44 solar masses) and annihilates itself in a thermonuclear detonation (right). Image: ESO.

Discovered in August this year and challenging our understanding of these stellar phenomena, this type of supernovae belongs to a family of violent eruptions whose dazzling brightness have served astronomers well in their attempts to unlock the mysteries hidden by the Universe. “Type Ia supernovae are standard candles with a well-defined intrinsic luminosity and when we find this type of supernova, we measure the apparent brightness,” says Mansi Kasliwal, a Hubble and Carnegie Princeton Fellow at the Carnegie Institution for Science, Pasadena. “The difference between the intrinsic luminosity and apparent brightness tells us how far away the supernova is and this gives us a cosmological yardstick. Combining measurements of several hundred events, we can determine that the Universe is accelerating.”

“For several years, I had been taking images with robotic telescopes at Palomar Observatory of the Pinwheel Galaxy every night I possibly could, hoping it would give birth to a rare cosmic feat,” says Kasliwal. “When we saw SN2011fe, I fell off my chair as its brightness was too faint to be a supernova and too bright to be nova. Only follow-up observations in the next few hours revealed that this was actually an exceptionally young Type Ia supernova.” But how could the team be sure that they had come across a young explosion? “Type Ia supernovae have a characteristic light curve; they rise from nothing to maximum brightness in roughly two and a half weeks and then start to fade,” he adds. “At the time we discovered this supernova, it was very faint, so we inferred it was young. As soon as we got the first spectrum, the characteristics of this spectrum (high temperature and large velocities) confirmed it was an infant.”

While the team, led by Professor Shri Kulkarni of the California Institute of Technology, had made a breakthrough with their discovery, they realised that SN2011fe was not your standard supernova, bucking the trend by disobeying widely accepted theories as to how it formed. Type Ia supernovae are generally believed to result from a white dwarf robbing too much material from its stellar orbital dance partner, causing these bright pint-sized stars to erupt in an enormous explosion. However on closer inspection through early radio and X-ray observations, along with a comparison with an analysis of historical images, a different story was starting to unfold - one that saw two models vying for the lead role; the so-called double-degenerate (or DD) model and the single-degenerate (or SD) model. The DD-model sees two white dwarfs battling it out causing the orbit between them to shrink until the light-weight of the two loses the fight and ends up getting swallowed by its companion leading to a characteristic explosion, whereas the SD model represents the detonation of a white dwarf which has bitten off more than it can chew by stealing material from a larger star such as a red giant.

It seems remarkable that the final moments of two doomed stars can be cobbled together after they have exploded, but it is all down to the debris that their destruction expels into space. “The interaction of the matter with the surrounding medium is a clue about the nature of the companion,” says Kasliwal. With their results, the team knew which theory was set to write the history of SN2011fe. “The DD-model says the companion is a white dwarf whereas the SD-model says the companion is either a red giant or a main sequence star or a helium star,” concludes Kasliwal, who is a co-author of a paper that details the research in The Astrophysical Journal. “We can convincingly rule out a red giant companion and helium star companion based on both the data before and just after the explosion. The most likely explanation here is that the companion to the exploding white dwarf was a main sequence star. Some models predict a brightening in the light curve in the early stages if it was two white dwarfs, which we do not see in our data.”

|

|

|

|

|