Two supernovae provide two flavours of neutron star

GEMMA LAVENDER

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: 17 November 2011

Researchers from the universities of Southampton and Oxford have taken a step back to the most fundamental processes of stellar evolution by uncovering evidence that two flavours of neutron star are the end product of two different supernova mechanisms.

Weighing in at around two times the mass of the Sun, neutron stars are stellar remnants that can often be the result of three different types of supernovae; Type II, Type 1b and Type 1c. With an entire composition of neutrons – subatomic particles without electrical charge – these stars might be hefty, but their weight can be squeezed into a ball at a diameter smaller than the city of London.

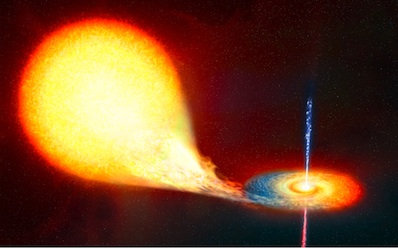

An artist’s impression of an X-ray binary. Image: ESA.

For some time, astronomers have only been able to speculate about the possibility of different types of neutron stars existing, and identifying two distinct families of neutron star has proven difficult for quite some time. “Basically, it’s just that all neutron stars are alike – once the core of a massive star has collapsed into a neutron star, almost all ‘memory’ of what it once was has been erased,” says Christian Knigge at the University of Southampton whose paper appeared electronically in Nature. “Now the reason that there should be two families is that there are these two different classes of supernovae [so-called ‘electron capture supernovae’ and ‘iron-core-collapse’ supernovae]. But the neutron stars they leave behind don’t really look very different.”

The supernovae responsible for the finding have dissimilarities of their own. For one, an iron-core-collapse supernova occurs when a high-mass star develops a degenerate iron core that exceeds 1.44 solar masses (the so-called Chandrasekhar limit), whereas an electron-capture supernova is associated with the collapse of a lower-mass oxygen-neon-magnesium core as it loses pressure support due to the sudden capture of electrons by neon and, on some occasions, magnesium nuclei. It seemed that, by taking and analysing a large sample of X-ray binaries, things began to look up in the way of turning the theory into a reality.

X-ray binaries are double star systems containing a fast-spinning neutron star that orbits its companion, a young massive star. Astronomers often find that the neutron star in this pairing steals material from its partner on a regular basis, causing the stellar thief to become an X-ray binary. With its periodical siphoning comes an incredible increase in brightness, resulting in X-ray radiation that is pulsed on the heavy-weight star’s spin period. While this behaviour does not look too good for the young star, Knigge along with his Southampton University colleague Malcolm Coe and Oxford University’s Phillip Podsiadlowski, found it quite useful as they set about timing the pulses, thus measuring the neutron’s spin cycle. “Our work here uses a data base of X-ray pulsar parameters that was compiled over several years and is based on observational data obtained,” says Knigge. “Those observations were based on a wide variety of ground- and space-based observations. The latter, in particular, include the Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer, Chandra and XMM.”

An artist’s impression of a supernova. Image: NASA/Swift/Skyworks Digital/Dana Berry.

What the team found was quite surprising and confirmed many astronomers’ suspicions as they uncovered that one grouping of neutron star spun once every 10 seconds while the other once every 5 minutes. “What this means physically is of course open to interpretation,” says Knigge. “Ours is that these two groups correspond to two types of supernovae. One reason for this is that we found a tantalizing hint in our data that the binary orbits of the fast-spinning pulsars are less elliptical than those of the slow-spinning ones. The easiest way to produce such ellipticity is via the kick imparted to the neutron star during the supernova event – this suggests the two populations are associated with different kinds of supernovae [since those produce different amounts of kick].”

As for the future of our understanding of stellar evolution, Knigge concludes, “these findings lead us to question how supernovae actually work. This opens up numerous new research areas, both on the observational and theoretical fronts.”

|