Asteroid Lutetia a rare survivor of Earth's birth

DR EMILY BALDWIN

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: 11 November 2011

Using ESA's Rosetta spacecraft, ESO's New Technology Telescope, and NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility and Spitzer Space Telescope to scrutinize the composition of asteroid Lutetia, astronomers have found that the 100 kilometre wide rock may represent one of the rarest types of asteroid that went into building the Solar System's innermost planets.

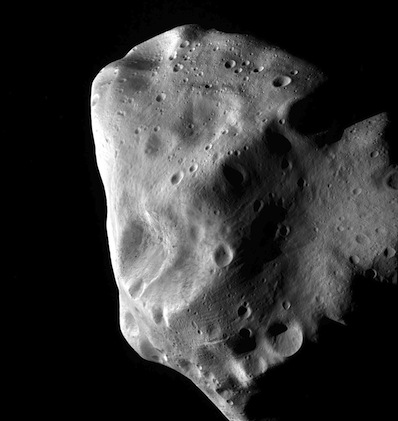

ESA's Rosetta spacecraft snapped this close-up shot of mysterious Lutetia in July 2010. Image: ESA 2010 MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

Previous studies of the asteroid had already highlighted its unusual nature, showing that it belongs to a family of asteroids that represent less than one percent of the asteroid belt's population.

The new data of the asteroid's surface closely matches the properties of a rare kind of meteorite found on Earth – enstatite chondrites – known to date from the early Solar System. Formed near the young Sun, enstatite chondrites are thought to have acted as a primary ingredient to build the rocky planets Mercury, Venus and Earth. Lutetia, therefore, provides a rare insight into the pristine material that went into building our home planet.

Yet Lutetia currently resides in the asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter.

Asteroid Lutetia could have received a gravitational slingshot from the inner Solar System to the asteroid belt from a nearby newly forming planet. Image: ESO/M. Kornmesser and N. Risinger.

"How did it escape from the inner Solar System and reach its current location?" asks ESO's Pierre Vernazza, lead author of a paper describing the results that will appear in the journal Icarus. Vernazza and his team suspect that sizeable Lutetia got caught up in the gravitational tug-of-war between the newly forming planets – including Jupiter – as they jostled into their current orbits, tossing it into a new location.

“We think that such an ejection must have happened to Lutetia. It ended up as an interloper in the main asteroid belt and it has been preserved there for four billion years,” adds Vernazza. “Lutetia seems to be the largest, and one of the very few, remnants of such material in the main asteroid belt. For this reason, asteroids like Lutetia represent ideal targets for future sample return missions. We could then study in detail the origin of the rocky planets, including our Earth.”

|