|

|

White dwarf planet not so Snow White

GEMMA LAVENDER

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: 24 August 2011

Researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have uncovered ice and possibly a thin atmospheric layer of methane belonging to the dwarf planet 2007 OR10, also nicknamed Snow White.

Despite the planet sporting a red tint, the name originally stuck due to water ice that covers half of its surface, believed to have once flowed from slush-spewing ancient volcanoes leading scientists to presume white frosty features.

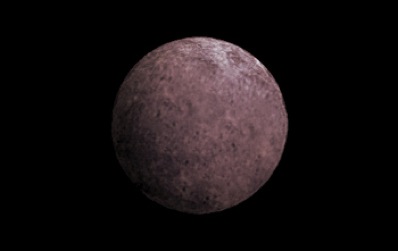

An artist's conception of 2007 OR10, nicknamed Snow White. Astronomers suspect that its rosy colour is due to the presence of irradiated methane. Image: NASA.

“You get to see this nice picture of what once was an active little world with water volcanoes and an atmosphere, and it’s now just frozen, dead, with an atmosphere that’s slowly slipping away,” says Mike Brown, the Richard and Barbara Rosenberg Professor and professor of planetary astronomy at Caltech, and who is lead author on a paper that details the findings which are due to be published in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Snow White was discovered in 2007 orbiting the Sun at the edge of the Solar System and is around half the size of Pluto, securing its place as the fifth largest dwarf planet ever found. At the time of its discovery Mike Brown incorrectly guessed that the planet was an icy body that had broken off from dwarf planet, Haumea, resulting in a presumption that 2007 OR10 was purely white. However, further observations of the distant dwarf shook off any notion of the planet living up to its name. Far from being pure white, Snow White was found to be one of the reddest objects in the Solar System, alongside other distant dwarf planets, known as Kuiper Belt Objects (KBO), residing on the outskirts of our planetary system sporting their red tints.

“With all of the dwarf planets that are this big, there’s something interesting about them – they always tell us something,” says Brown. “This one frustrated us for years because we didn’t know what it was telling us.” At the time of the dwarf planet’s discovery, the Near Infrared Camera (NIRC) at the Keck Observatory was the best instrument that scientists had to study these distance objects, but since its recent retirement, observing Snow White in details was a challenge. “It kind of languished,” he adds.

It was not until the design of a new instrument called the Folded-port Infrared Echellette (FIRE) by Adam Burgasser, a former graduate student of Brown's and now a professor at UC San Diego, that further study of the dwarf planet could be made. With the combined efforts of Brown, Burgasser and postdoctoral scholar Wesley Fraser, and aided by the new instrument along with the 6.5-metre Magellan Baade Telescope in Chile, their perception of the planet changed even further.

While they discovered that Snow White was red, the dwarf planet's spectrum, quite interestingly, pointed to the existence of water ice covering its surface. “That was a big shock,” says Brown. “Water ice is not red.” While ice is common throughout the outer Solar System due to the freezing temperature, it is usually white – just how it appears on Earth.

Despite the mysterious finding, Snow White is not alone. Quaoar, a slightly smaller dwarf planet that was discovered along with the assistance of Brown in 2002, also proves to be just as peculiar, displaying a red surface despite being hugged by water ice. Although it is smaller than 2007 OR10, Quaoar is still large enough to hold onto an atmosphere and possess volcanoes which pepper its surface, oozing an icy slush that later froze as it snaked across the planet's exterior. However, the small planet is incapable of hanging onto volatile compounds such as methane, carbon monoxide or nitrogen – at least, not for long. A couple of billion years after its formation, Quaoar began to lose its atmosphere to outer space, leaving behind traces of methane which serve as clues to the process.

But what causes Quaoar's rosy complexion? Scientists believe that, over time, this methane (which consists of a carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms) was converted into long hydrocarbon chains due to the exposure of intense space radiation, leaving a warm red hue which sits on Quaoar's frosty surface.

Comparing Quaoar and Snow White's spectra, the similarities were striking, suggesting that what occurred on Quaoar also happened on 2007 OR10. “That combination – red and water – says to me, 'methane',” says Brown. “We're basically looking at the last gasp of Snow White. For four and a half billion years, Snow White has been sitting out there, slowly losing its atmosphere, and now there's just a little bit left.”

But the study is not over; although the 2007 OR10's spectrum clearly shows the presence of water ice, evidence for methane is still not yet definitive. Further studies using a large telescope similar to the Keck Observatory's is necessary in order for scientists to determine if the dwarf planet is holding methane to it's surface.

Since the dwarf can no longer hold onto its nickname due to it's rosy hue, Brown believes that it should be renamed to something more fitting. “We didn't know Snow White was interesting,” concludes Brown. “Now we know it's worth studying.”

|

|

|

|

|