MESSENGER heads for third Mercury encounter

DR EMILY BALDWIN

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: September 29, 2009

NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft will make its third and final pass of innermost planet Mercury tonight, on a gravity assist maneuver that will steer it into orbit around the Sun-drenched world in March 2011.

This image was captured yesterday as MESSENGER approaches the rocky planet for the third time. Image: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

This image was captured yesterday as MESSENGER approaches the rocky planet for the third time. Image: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

The spacecraft will speed past Mercury's surface at an altitude of 228 kilometres and at over 160,000 kilometres per hour. During this sweeping glance MESSENGER's seven instruments – a camera, a magnetometer, an altimeter and four spectrometers – will capture high resolution colour images and measurements of targets picked out from the previous two flybys. Another five percent of the planet's surface will be imaged for the first time, bringing the mapped area close to one hundred percent.

“We will be pointing at each individual target from several different angles during the flyby, which will allow us to collect more data,” says William McClintock, a MESSENGER mission co-investigator who led the development of the Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer (MASCS).

The MASCS team is particularly interested in unusual surface deposits spotted by the camera during MESSENGER’s previous flybys,“One of the big questions planetary scientists have is how much iron there is on Mercury’s surface,” says McClintock. “We hope to pinpoint the iron, determine what chemical form it is in and how it is bound up on the planet’s surface.”

Mercury's core is dominated by iron, which is responsible for maintaining the planet’s magnetic field. The planet's surface is much darker than the Moon’s, indicating that there should be a high iron and/or titanium content. This is thought to be in the form of ilmenite, an iron-titanium oxide, or nanophase iron, which gets distributed on the surface because of space weathering, whereby high energy particles from the solar wind, or micrometeorites, impinge on the planet's surface, changing the optical and physical properties of minerals there.

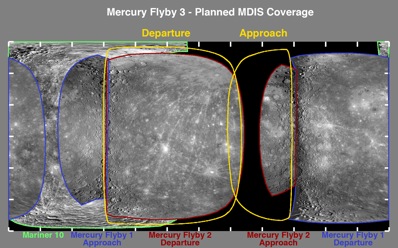

During tonight's flyby, the area outlined in yellow will be imaged by the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), and includes never-before-seen terrain of the innermost planet. Image: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

During tonight's flyby, the area outlined in yellow will be imaged by the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), and includes never-before-seen terrain of the innermost planet. Image: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

“We will sample a composition on this side of the planet that could be very different from what we saw on the other side of the planet during the first flyby,” says William Feldman, Co-Investigator for MESSENGER's Neutron Spectrometer. “It would be very surprising if we found the exact same composition that we saw on that first flyby.”

On missions to the Moon and Mars neutron spectrometers have found evidence for the presence of water molecules, and both the Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer on MESSENGER will search for hydrogen as a possible indicator for water deposits in the cold polar regions of Mercury that never receive full sunlight.

After this third and final flyby MESSENGER will have collected the same amount of data as during a single orbit around Mercury. Once MESSENGER settles into a yearlong pattern of twice daily orbits around Mercury in 2011, analysing the massive streams of images and data “will be like drinking from a fire hose,” says McClintock.

|