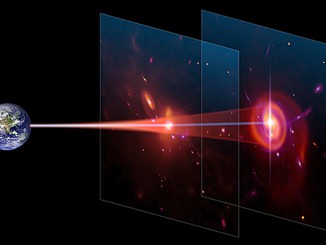

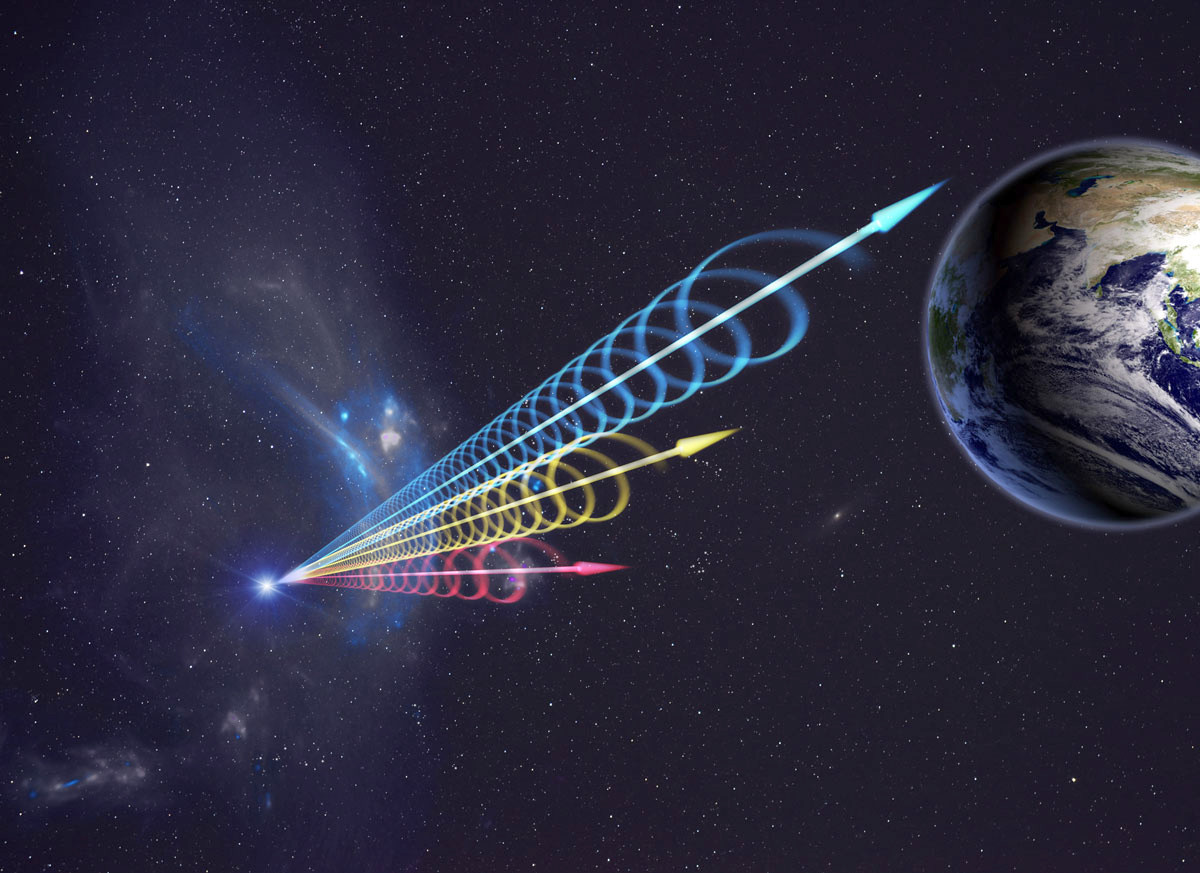

“Because FRBs like the one we discovered occur billions of light-years away, they help us study the universe between us and them,” says Caltech postdoctoral scholar Vikram Ravi, who is the R A and G B Millikan Postdoctoral Scholar in Astronomy. “Nearly half of all visible matter is thought to be thinly spread throughout intergalactic space. Although this matter is not normally visible to telescopes, it can be studied using FRBs.”

The most luminous FRB to date, called FRB 150807, appears to only be weakly distorted by material within its host galaxy, which shows that the intergalactic medium in this direction is no more turbulent than theorists originally predicted. This is the first direct insight into turbulence in intergalactic medium.

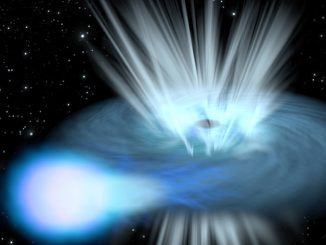

The researchers observed FRB 150807 while monitoring a nearby pulsar — a rotating neutron star that emits a beam of radio waves and other electromagnetic radiation — in our galaxy using the Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia. “Thanks to a real-time detection system developed by the Swinburne University of Technology, we found that although the FRB is a million times further away than the pulsar, the magnetic fields in their directions appear identical,” says Ryan Shannon, research fellow at Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Astronomy and Space Science and at Curtin University in Australia, and colead author of the study. This refutes some claims that FRBs are produced in dense environments with strong magnetic fields. The result provides a measure of the magnetism in the space between galaxies, an essential step in determining how cosmic magnetic fields are produced.

Only 18 FRBs have been detected to date. Mysteriously, most give off only a single burst and do not flash repeatedly. Additionally, most FRBs have been detected with telescopes that observe large swaths of the sky but with poor resolution, making it difficult to pinpoint the exact location of a given burst. The unprecedented brightness of FRB 150807 allowed Ravi and his team to localise it much more accurately, making it the best-localised FRB to date.

In February 2017, pinpointing the locations of FRBs will become much easier for astronomers with the commissioning of the Deep Synoptic Array prototype, an array of 10 radio dishes at Caltech’s Owens Valley Radio Observatory in California.

“We estimate that there are between 2,000 and 10,000 FRBs occurring in the sky every day,” Ravi says. “One in 10 of these are as bright as FRB 150807, and the Deep Synoptic Array prototype will be able to pinpoint their locations to individual galaxies. Measuring the distances to these galaxies enables us to use FRBs to weigh the tenuous intergalactic material.”