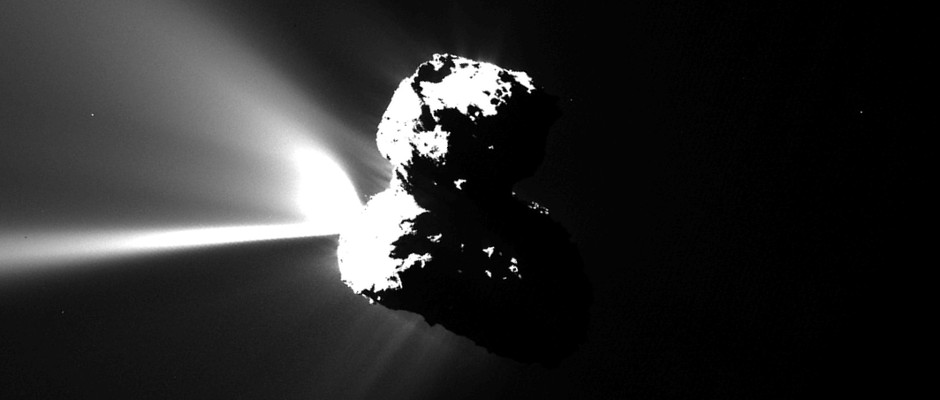

In the year that has passed since Rosetta arrived, the comet has travelled some 750 million kilometres along its orbit towards the Sun, the increasing solar radiation heating up the nucleus and causing its frozen ices to escape as gas and stream out into space at an ever greater rate. These gases, and the dust particles that they drag along, build up the comet’s atmosphere – coma – and tail.

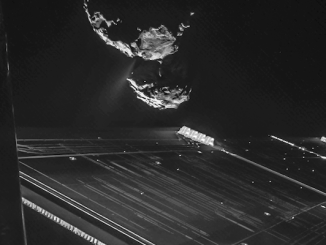

The activity reaches its peak intensity around perihelion and in the weeks that follow – and is clearly visible in the spectacular images returned by the spacecraft in the last months. One image taken by Rosetta’s navigation camera was acquired at 2:04am GMT, just an hour before the moment of perihelion, from a distance of around 327 kilometres (203 miles).

The scientific camera is also taking images yesterday – the most recent available image was taken at 12:31am BST on 13 August, just a few hours before perihelion. The comet’s activity is clearly seen in the images, with a multitude of jets stemming from the nucleus, including one outburst captured in an image taken at 6:35pm BST on 12 August.

Rosetta’s measurements suggest the comet is spewing up to 300kg of water vapour – roughly the equivalent of two bathtubs – every second. This is a thousand times more than was observed this time last year when Rosetta first approached the comet. Then, it recorded an outflow rate of just 300g per second, equivalent to two small glasses of water.

Along with gas, the nucleus is also estimated to be shedding up to 1000kg of dust per second, creating dangerous working conditions for Rosetta.

“In recent days, we have been forced to move even further away from the comet. We’re currently at a distance of between 325 and 340 kilometres this week, in a region where Rosetta’s startrackers can operate without being confused by excessive dust levels – without them working properly, Rosetta can’t position itself in space,” comments Sylvain Lodiot, ESA’s spacecraft operations manager.

Inside the magazine

Find out more about Rosetta’s first year at the comet in the August 2015 issue of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue of the UK’s biggest and longest running astronomy magazine by subscribing. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.