Galaxies grow by churning loose gas from their surroundings into new stars, or by swallowing neighbouring galaxies whole. However, they normally leave very few traces of their cannibalistic habits.

Galaxies grow by churning loose gas from their surroundings into new stars, or by swallowing neighbouring galaxies whole. However, they normally leave very few traces of their cannibalistic habits.

A study published May 20th in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS) not only reveals a spiral galaxy devouring a nearby compact dwarf galaxy, but shows evidence of its past galactic snacks in unprecedented detail.

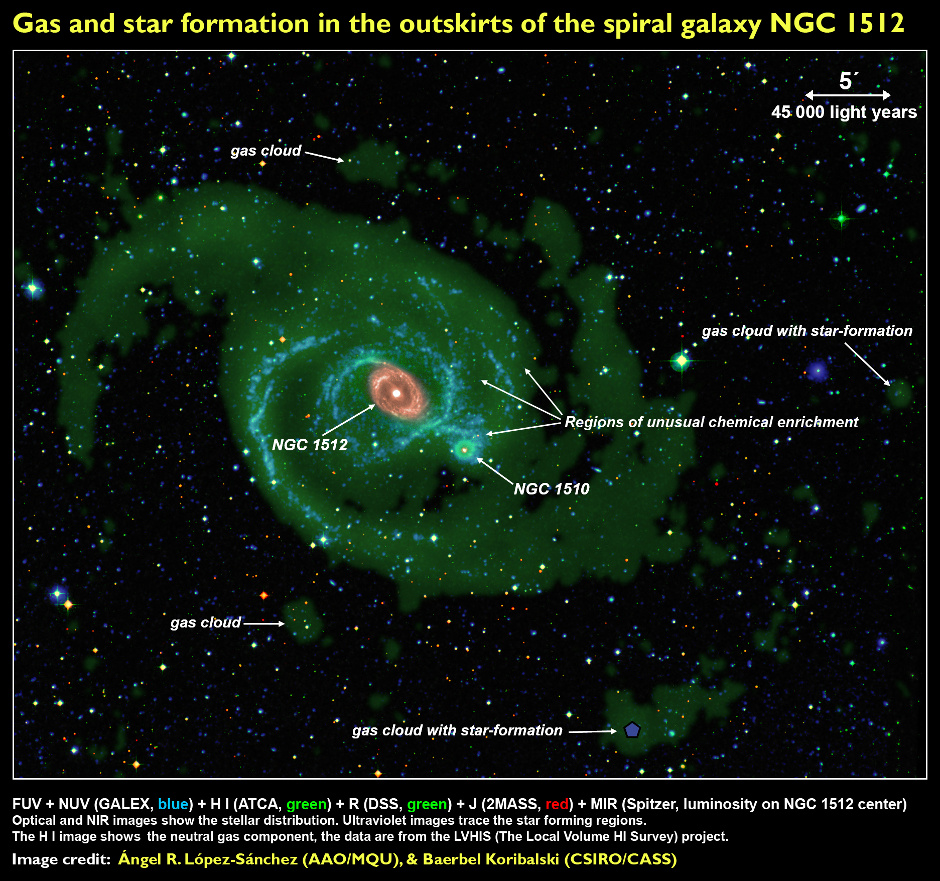

Australian Astronomical Observatory (AAO) and Macquarie University astrophysicist, Ángel R. López-Sánchez, and his collaborators have been studying the galaxy NGC 1512 to see if its chemical story matches its physical appearance.

The team of researchers used the unique capabilities of the 3.9-metre Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT), near Coonabarabran, New South Wales, to measure the level of chemical enrichment in the gas across the entire face of NGC 1512.

Chemical enrichment occurs when stars churn the hydrogen and helium from the Big Bang into heavier elements through nuclear reactions at their cores. These new elements are released back into space when the stars die, enriching the surrounding gas with chemicals like oxygen, which the team measured.

“We were expecting to find fresh gas or gas enriched at the same level as that of the galaxy being consumed, but were surprised to find the gases were actually the remnants of galaxies swallowed earlier,” Dr. López-Sánchez said.

“The diffuse gas in the outer regions of NGC 1512 is not the pristine gas created in the Big Bang but is gas that has already been processed by previous generations of stars.”

CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array, a powerful 6-kilometre diameter radio interferometer located in eastern Australia, was used to detect large amounts of cold hydrogen gas that extends way beyond the stellar disc of the spiral galaxy NGC 1512.

“The dense pockets of hydrogen gas in the outer disc of NGC 1512 accurately pin-point regions of active star formation,” said CSIRO’s Dr. Baerbel Koribalski, a member of the research collaboration.

Dr. Tobias Westmeier, from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth, said that while galaxy cannibalism has been known for many years, this is the first time that it has been observed in such fine detail.

“By using observations from both ground- and space-based telescopes we were able to piece together a detailed history for this galaxy and better understand how interactions and mergers with other galaxies have affected its evolution and the rate at which it formed stars,” he said.

The team’s successful and novel approach to investigating how galaxies grow is being used in a new program to further refine the best models of galaxy evolution.

For this work the astronomers used spectroscopic data from the AAT at Siding Spring Observatory in Australia to measure the chemical distribution around the galaxies. They identified the diffuse gas around the dual galaxy system using Australian Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) radio observations. In addition, they identified regions of new star formation with data from the Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) orbiting space telescope.

“The unique combination of these data provide a very powerful tool to disentangle the nature and evolution of galaxies,” said Dr. López-Sánchez. “We will observe several more galaxies using the same proven techniques to improve our understanding of the past behavior of galaxies in the local universe.”