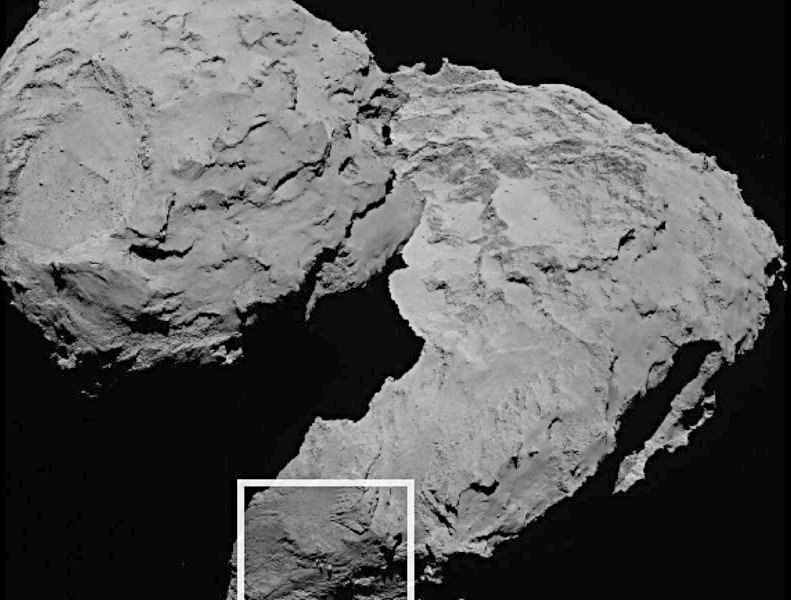

Similar geological formations are found also on Earth. So-called balancing rocks touch the underground with only a tiny fraction of their surface and often look as if they may tilt or topple over any moment. Some can actually be rocked back and forth and are then referred to as “rocking stones.” Impressive examples of balancing rocks occur in Australia or the southwest of the USA. Often these boulders travelled to their current location onboard of glaciers. In other cases, wind and water eroded softer material surrounding the rock.

“How the potential balancing rock on the comet was formed, is not clear at this point,” says OSIRIS Principal Investigator Holger Sierks from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany. It is possible that also on 67P transport processes did their part. The comet’s activity may cause such boulders to move and thus reach a new location.

“We had noticed this formation already in earlier images,” says OSIRIS scientist Sebastien Besse from ESA, who discovered the possible balancing rock. “However, at first the boulders did not seem to differ substantially from other we had seen.” Scattered boulders can be found in many places on the comet’s surface. One of the largest ones measures approximately 45 metres. In reference to the Egyptian pyramids, the scientists dubbed it “Cheops.” Other regions on 67P resemble a rubble pile and are practically covered by boulders.

“Interpreting images of the comet’s surface can be tricky,” says Sierks. Depending on the viewing angle, illumination, and spatial resolution very different and sometimes even misleading impressions are created.

The OSIRIS scientists intend to continue to monitor the potential balancing rock carefully. New images might give insights into its true nature and maybe even its origin.