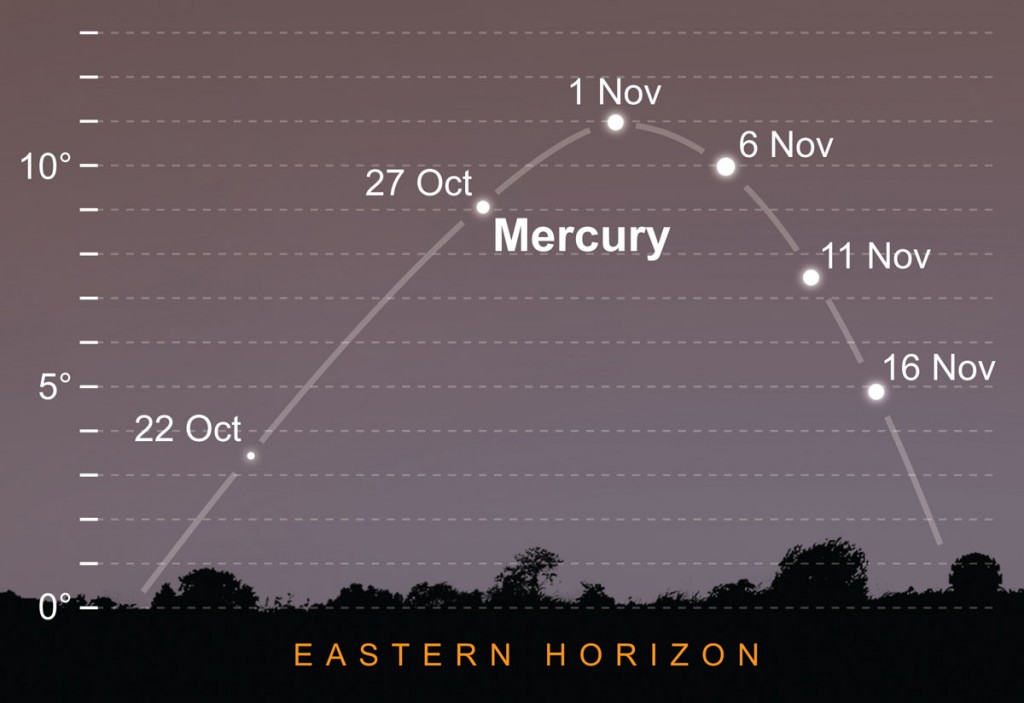

If you’ve never seen the Solar System’s innermost planet before, now is your chance, as long as early morning starts don’t worry you! Mercury is currently making a very favourable showing in the pre-dawn sky, It’s the best opportunity for Northern Hemisphere observers to catch the fleet-footed planet this year.

Mercury has been pulling west of the Sun since it was at inferior conjunction on 16 October, brightening all the way and gradually hauling clear of the east-south-east horizon. It reaches greatest elongation this weekend (19 degrees on 1 November).

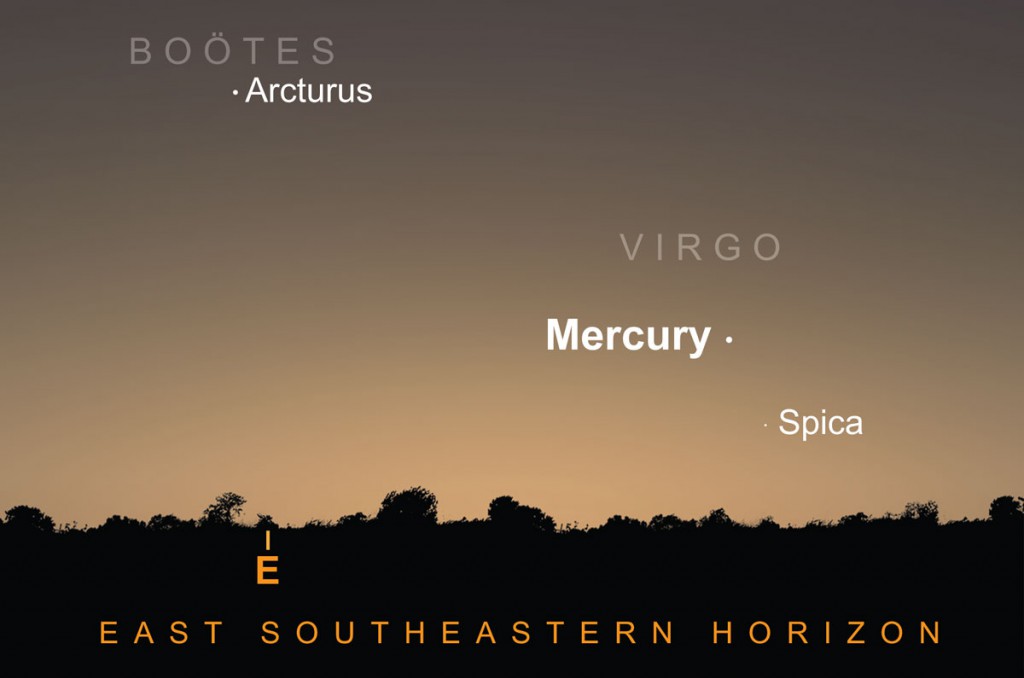

It should be visible about an hour before sunrise (5.45am UT in London) with an unobstructed view of the horizon. Shining at magnitude –0.43, it is by far the brightest object in this area of the sky, outshining Arcturus, 15 or so degrees further east and first magnitude Spica, which lies six degrees below Mercury and is just about to rise; Mercury lies close to theta Virginis (mag. +4.4).

Mercury will have climbed to an altitude of 10 degrees some 30 minutes later at 6.15am, the start of civil twilight from London when the Sun is six degrees below the horizon; town dwellers will hopefully be able to find a viewing spot where Mercury can be spied between the roof and tree tops.

Mercury is too tiny in apparent diameter to show off its phases in binoculars but just to see it is reward enough. A small telescope will show the planet as a little more than half-illuminated disc, like a first or last quarter Moon.

Astronomy Now’s Peter Grego reports that Mercury’s seven arcsecond disc is sufficiently large to yield some dusky surface markings through a 100-mm (four-inch) apochromat refractor, a 125-mm (five-inch) Maksutov Cassegrain or a 150-mm (six-inch) Newtonian reflector. Peter recommends using colour filters to help improve the view; try an orange (W21) or red (W23A, W25 or W29).

The advantage of morning apparitions is of course that the planet can be followed and observed in daylight as it further clears the horizon and before the seeing deteriorates with the Sun’s increasing influence. Great care must be taken if you are going to search for Mercury when the Sun has already risen, as one inadvertent look at the Sun in the eyepiece could seriously or even permanently damage your eyesight.

Mercury remains a viable observing target for the first half of November; by mid month it shines at mag. -0.8 and displays a gibbous phase spanning 5.2 arcseconds and 90 percent illuminated.

Try to make the most of this opportunity as it won’t be this well placed again until late spring. Astronomy Now would be delighted to receive any images; please send them to gallery2014 @ astronomynow.com

Inside the magazine

You can read more about the Mercury’s final curtain call of 2014 in the November issue of Astronomy Now as part of our complete guide to the night sky. Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s longest running astronomy magazine.