|

Top Stories

|

|

|

|

First measurements of the termination shock First measurements of the termination shock

...as intrepid Voyager 2 passed through the solar wind termination shock, the local STEREO spacecraft detected particles emanating from the same distant location...

read more

The stars and stripes of the Universe

...a delicate ribbon of gas floats eerily in the Milky Way, a ghostly reminder of a

supernova explosion that occurred over 1,000 years ago...

read more

Cluster listens to the sounds of the Earth

...Cluster has been tuning into the Earth's aurora, listening out for a signal that may help in the search for alien worlds...

read more

|

|

|

|

Spaceflight Now +

|

|

|

|

Subscribe to Spaceflight Now Plus for access to our extensive video collections!

How do I sign up? How do I sign up?

Video archive Video archive

STS-120 day 2 highlights

Flight Day 2 of Discovery's mission focused on heat shield inspections. This movie shows the day's highlights.

Play Play

STS-120 day 1 highlights

The highlights from shuttle Discovery's launch day are packaged into this movie.

Play Play

STS-118: Highlights

The STS-118 crew, including Barbara Morgan, narrates its mission highlights film and answers questions in this post-flight presentation.

Full presentation Full presentation

Mission film Mission film

STS-120: Rollout to pad

Space shuttle Discovery rolls out of the Vehicle Assembly Building and travels to launch pad 39A for its STS-120 mission.

Play Play

Dawn leaves Earth

NASA's Dawn space probe launches aboard a Delta 2-Heavy rocket from Cape Canaveral to explore two worlds in the asteroid belt.

Full coverage Full coverage

Dawn: Launch preview

These briefings preview the launch and science objectives of NASA's Dawn asteroid orbiter.

Launch | Science Launch | Science

Become a subscriber Become a subscriber

More video More video

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anaemic Mercury dominated by volcanism

BY DR EMILY BALDWIN

ASTRONOMY NOW

Posted: July 4, 2008

In January 2008, MESSENGER became the first probe to fly past the planet Mercury in 33 years. In a special edition of Science released today, 11 papers describe the findings of that flyby, revealing the innermost planet of our Solar System as surprisingly deficient in iron, and having suffered a decidedly volcanic past.

"It's like we did a forensic analysis of Mercury. This flyby got the first-ever look at surface composition. We now know more about what Mercury's made of than ever before. Holy cow, we found way more than we expected!” Thomas Zurbuchen, University of Michigan.

|

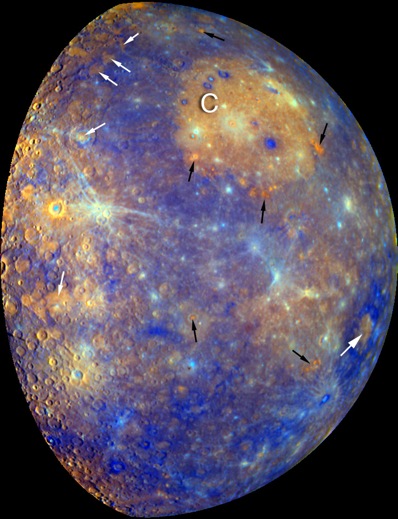

At first glance Mercury looks a lot like Earth’s heavily cratered Moon, but new multispectral images from MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) show that volcanism has played a much larger role in the planet’s evolution than previously anticipated. The massive Caloris impact basin, which covers at least a million square kilometres, is displayed as an orange stain in the multispectral images, revealing low-iron concentration lavas that must have been provided by a large source of magma residing in Mercury’s upper mantle. The multispectral images also show a number of volcanic ‘red spots’ dotted around the Caloris basin and elsewhere on the Mercury’s surface, sometimes coinciding with holes in the ground, indicative of an explosive form of volcanic eruption.

"According to our colour data the Caloris impact basin is completely filled with smooth plains material that appears volcanic in origin," says Mark Robinson of Arizona State University. "In shape and form these deposits are very similar to the mare basalt flows on the Moon. But unlike the Moon, Mercury's smooth plains are low in iron, and thus represent a relatively unusual rock type."

Low-iron volcanic plains fill the Caloris impact basin (marked 'C') which is revealed as a rusty orange colour in this multispectral image of Mercury. White arrows mark the locations of young smooth plains whose composition appears related to the Caloris plains. Black arrows mark the location of 'red spots', possible volcanic centres. The widespread dark blue regions are older rocks. Image: NASA/JHUAP/Arizona State University.

Even though tiny Mercury is more than 60 percent iron by weight, thanks to a core at least twice the size than that found in any other planet, one of the most surprising findings of the first MESSENGER flyby is that the planet’s surface is oddly iron-poor. By inference, describes one report lead by Sean Solomon of the Carnegie Institution, this means that the abundance of iron in the mantle is also low.

Robinson’s research team, which is made up of 12 additional researchers from other institutions, describes Mercury as having a relatively low reflectance surface, with three major rock units that stand out corresponding to relatively high reflectance volcanic smooth plains, average cratered terrain, and low reflectance material. “The low reflectance material is particularly enigmatic,” says Robinson. "It's an important and widespread rock that occurs deep in the crust as well as at the surface, yet it has very little ferrous iron in its silicate minerals." This defies natural expectation that low reflectance volcanic rocks have a high abundance of iron-bearing silicate minerals. One possible solution, say Robinson et al, is that iron is actually present but invisible to MESSENGER's spectrometers because it is hidden within the chemical structure of other minerals.

"If you want to understand how a planet has evolved," says Robinson, "you need to know about the minerals in its crust and mantle. Unfortunately, we are not going to be able to drill into Mercury for a long time to come. All we can do is study its volcanic rocks in detail. They give a glimpse into the planet's mantle." Robinson’s team believe that Mercury formed with a deficiency in ferrous iron, but more will be revealed once MESSENGER goes into orbit in 2011, allowing scientists to study the surface rocks in much more detail.

Possible embayment of cliffs (white arrows) by smooth, volcanic plains material. The formation of these scarps tells planetary scientists about the cooling history, and hence the magnetic dynamo, of Mercury. The black arrow points to a young crater that has not been affected by lava flows. Image: Solomon at al, Science, 4 July 2008.

In a different study, scientists from the University of Michigan who built the Fast Imaging Plasma Spectrometer (FIPS) instrument report on measurements of charged particles in Mercury’s magnetic field, and paint a picture of how the magnetic field and solar wind interact with the planet’s surface and thin atmosphere. FIPS detected silicon, sodium, sulphur and even water ions around Mercury. The FIPS team speculate that these molecules were blasted from the surface by the solar wind, which given its proximity to the Sun, causes particles from Mercury’s surface and atmosphere to sputter into space.

"The Mercury magnetosphere is full of many ionic species, both atomic and molecular, and in a variety of charge states,” says Thomas Zurbuchen, FIPS project leader. “What is in some sense a Mercury plasma nebula is far richer in complexity and makeup than the Io plasma torus in the Jupiter system.”

Finally, one of the biggest debates surrounding the source of Mercury’s magnetic field has finally been settled. The flyby revealed that the magnetic field, originating in the outer core and powered by core cooling, drives very dynamic and complex interactions between the planet’s interior, surface, atmosphere and magnetosphere. Sean Solomon explains the interaction: "The dominant tectonic landforms on Mercury, including areas imaged for the first time by MESSENGER, are features called lobate scarps, huge cliffs that mark the tops of crustal faults that formed during the contraction of the surrounding area. They tell us how important the cooling core has been to the evolution of the surface. After the end of the period of heavy bombardment, cooling of the planet's core not only fueled the magnetic dynamo, it also led to contraction of the entire planet. And the data from the flyby indicate that the total contraction is a least one-third greater than we previously thought."

The next Mercury flyby will be on October 6 this year, and the third in September 2009, with a final insertion into orbit in March 2011. The fact that 11 papers worth of new research resulted from just a couple of days observations from the first flyby bodes well for the years MESSENGER will spend mapping and deciphering Mercury’s surface, and providing planetary scientists with more data than ever about the planet’s magnetic field and interaction with the solar wind.

|

|

|

|

|

|